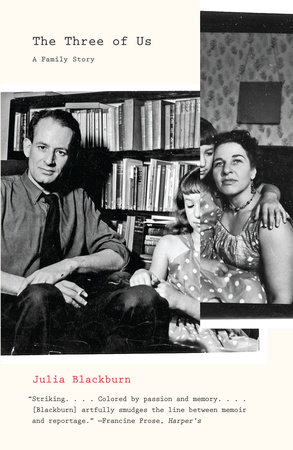

This IsThis is the story of three people. It is the story of my two parents and the three of us together, but it is also the story of the tangled fairy-tale triangle, which took shape between me and my mother and the succession of solitary men who entered our lives after my father had left. My father Thomas Blackburn was a poet and an alcoholic who for many years was addicted to a powerful barbiturate called sodium amytal, which was wrst prescribed for him in 1943. When the cumulative evect of the drug combined with the alcohol made him increasingly violent and so mad he began to growl and bark like a dog, he was tried out on all sorts of substitute pills, including one which he proudly said was used to tranquillize rhinoceroses. He had two divorces and several breakdowns, but then at the age of sixty he had a vision of the afterlife, which made him happy because he realized he was no longer afraid of dying. A year later, in the early morning of 13 August 1977, he finished writing a long letter to his brother with the words ‘I am now going to lie down in a horizontal position and breathe long and deep.’ He then went upstairs and died from a cerebral haemorrhage, just as he was getting into bed.He was disastrous in so many ways, yet I never felt threatened by him. I could be frightened of the madness and the drunken rages, but I never doubted the honesty of his relationship with me and that was what really mattered. My mother, Rosalie de Meric, was very diverent. She was a painter by profession and she rarely got drunk and didn’t use prescription drugs, and she was sociable and sane and xirtatious, and I was always afraid of her. Right from the start I was her sister and her conwdante and, eventually, her sexual rival, as the boundaries between us became increasingly dangerous and unclear. The battle we fought reached a crisis in 1966 when I was eighteen, and that crisis never really passed, the scent of rage and adrenaline hanging in the air as sharp as gunpowder. On the first day of March 1999, when she was eighty-two years old, my mother was told she had only a short time to live and she came to stay with me for what proved to be the last month of her life. Something crucial happened and the spell that had held us for so long in its grip like an icy winter was wnally broken, and we were able to laugh and talk together with an ease we had never known before. ‘I have never been so happy in all my life,’ she said. ‘How curious to be dying at the same time.’ And when she was near the end and her voice had become so slow and deep it seemed to be emerging from the bottom of a well, my mother said, ‘Now you will be able to write about me, won’t you!’ ‘Yes, I will,’ I replied, because in that moment I felt she was giving me her blessing, making it possible for me to tell a story that otherwise I could never have told. During her final month I kept a journal, which recorded this brief and joyful time. I also exchanged faxes with my old friend Herman, who was living in Holland. He had come to visit me just a couple of days before my mother learnt that she was ill. Herman and I had first been lovers in 1966 and we wnally parted in 1973. He was the one person who knew all about the past and how important it was to sort things out before it was too late. I have used excerpts from my journal and from the faxes throughout the telling of this story; they are the thread that connects the beginning to the end. Herman and I were married in December 1999. A Supper Party Friday, 2 April 1965 and I know the date because I still have the diary I kept for that year. The supper party was at my father’s house: the house where he now lived with my stepmother and her daughter and a black-and-white Parson Jack Russell terrier called Henry, whom I liked very much. Here I am at the front door of the house. I ring the bell and it makes an optimistic bing-bong, bing-bong noise, as if it were an ice-cream van telling the children to come and buy, quick, quick. There are thick panes of red and blue glass in the door and when I press my face to them I can just see a blue and red Henry dancing a welcome. My father is looming into view and I can hear his sharp cough. He opens the door. He is pasty-faced from all the pills and hangovers. His spectacles are low on his nose and he is gazing over the top of them with a lopsided smile, which was made lopsided ages ago when he climbed over a high spiked fence and fell and was caught by his upper lip on one of the spikes. He is wearing a beige cardigan that has cigarette burns in it and when he kisses me on the cheek I can smell Fisherman’s Friend extra strong cough sweets, as well as beer and wine and Capstan Full Strength cigarettes, untipped. ‘There you are, darling,’ he says, which is true, I am. ‘Come in, come in. How nice! You look well. Looked ghastly the last time I saw you. I’m just finishing something. Won’t be long. Peggy’s in the kitchen.’ And he’s gone, back to his study. I know that just last week, my father threw my stepmother into an empty bathtub. Naked, or at least I presume she was naked, although she might have been in her pyjamas. They were having a fight and the neighbours came because of all the shouting and screaming, but they didn’t call the police, not this time. ‘Imagine that,’ said my mother, who laughed when she told me the story. My mother had always been too heavy to be lifted or thrown, but she was punched and slapped instead. My father never hit me; except once when the three of us were sitting down to Sunday lunch at the big round table and he had lunged sideways at my mother with his wst, but got me instead by mistake. ‘So sorry darling,’ he said, genuinely apologetic. ‘No blood I hope?’ But now here’s Peggy and I can’t see any bruises. She also smells of cigarettes and wine, and she has her own sharp and foxy smell, which mixes with the sweetness of her perfume. She wears a lot of perfume and carries a lipstick with her wherever she goes. She has put some on now and her lips are dark red and shiny. She has a big wide mouth with very regular teeth, a sharp nose and almost lidless eyes like little almonds, that will flicker and close later, when the wine kicks in. Her black hair is cut in a bob with a fringe. She is shorter than me and delicately built, with thin wrists and narrow shoulders. Even I could pick her up if I chose to. She is wearing a green silk shirt. I’ve told the two of them that I’m going to stay the night. I have never stayed the night here before, but I’m having a lot of trouble at home with my mother, so I thought I’d give it a try and then, if it worked, I could move in and stay for a while. My father had been very pleased when I told him the first part of my plan. ‘Good, good, good!’ he said and he rubbed his hands together with a papery sound, which was one of his ways of expressing pleasure. There is a spare room and my stepmother leads me to it and opens the door. There are boxes of remaindered books of my father’s poetry on the xoor and a bedcover that I remember from long ago. The sheet has been turned down in readiness for my arrival. I go to the bathroom and open the medicine cupboard. I take out a pot of Elizabeth Arden rich moisturizing night cream and rub some on my face. I look at the bright colours of the lipsticks that stand higgledy piggledy in a corner of the cupboard and marvel at how they are all worn down to such a round blunt stub. I sniv at a bottle of my father’s Jochem’s Hair Oil. He used the same stuv when he lived with me and my mother. It’s got bay rum in it and a sweet smell that I like. I go down to the kitchen, which is very small, with just enough room for a sink and a cooker. Last week, maybe it was after the business with the bathtub, my father phoned to tell me he had thought of killing himself. He said he was going to gas himself in the cooker because he felt so depressed. At that moment Peggy had snatched the phone from him and I heard him grunting with surprise. ‘He turned on the gas,’ she said, ‘but when he saw the cold roast chicken in the oven, he ate it, all of it, at two o’clock in the morning. We had nothing for lunch the next day!’ My father reclaimed the phone. ‘I have been very depressed, darling. Black despair. The poems won’t come like they used to.’ Peggy is preparing things in the kitchen. She has bought half a dozen little pots of lumpwsh caviar and ham and cheese and salami and smoked salmon and lots of Jacobs Cream Crackers. Tonight’s supper is to be a long stream of hors d’oeuvres, with coffee and brandy to round it all off. My father has finished whatever he was doing in his study and he comes to join us, a full glass in his hand. ‘Drink?’ he says. ‘I’ve got sherry and Martini and lots of sweet German hock, which nobody likes except me.’ The table has been laid and the little bits and pieces of cold this and that are displayed on plates. David Wright, the deaf poet who wrote a poem about an Emperor Penguin, arrives with his wife Pippa. She is an actress and she has white skin and red hair, and she holds his hand all the time; later she even manages to keep hold of his hand while she is eating. David Wright talks in a booming monotone. His big face is solemn but curiously without expression and he keeps his eyes fixed on his wife and doesn’t try to understand what people are saying, but turns to her instead, so she can translate with her lips. According to my diary another couple is here as well, along with one of my father’s students from the college where he teaches, but they have all disappeared from my memory without trace. We sit on hard chairs round the table and we put things on our crackers, which splutter their jagged crumbs over the tablecloth and down on to our laps. David Wright booms and Peggy’s eyelids are xuttering and I am trying to impress everyone with my cleverness. I tell David Wright that I enjoyed his poem about the unhappy penguin in the London Zoo who didn’t appreciate how comfortable his life had become and missed the icy storms of the Antarctic. David Wright stares at me with blank incomprehension, then turns to his wife to translate my words for him. ‘Thank you,’ he says solemnly. I notice that my father’s bottom lip is getting looser. He has stopped eating and he is finding it increasingly difficult to locate his mouth with the end of a cigarette and impossible to light the cigarette once it is in position. He holds the flaring match head down, the xame burning the skin and nails of his thumb and forefinger and filling the room with a brief acrid smell. ‘Let me do it for you, Tom,’ says Pippa with the red hair, and he grins and holds his face close to hers, greedily sucking in anticipation of success. By now he is mixing red wine with the sweet German hock and adding a slosh of sherry as an afterthought. Peggy has also stopped eating. She stands behind him with her hands gripping his shoulders. ‘Darling!’ he says and pats her hand. ‘Darling!’ she says and moves her hand away. My father has read us a new poem and we have talked about William Blake and how he felt that death was nothing more than walking into the next room. We have also talked about the friability of Cream Crackers and whether salami is made out of donkeys, but the conversation is faltering. Henry has been watching things very closely and he senses that trouble is on its way. He turns on his heels and, with a short bark, demands to be let out of the room. ‘Stay here, damn you!’ says my father, a note of pleading in his voice. ‘That dog disapproves of me. He acts like a moral policeman.’ But Henry is insistent and when the door is opened for him he goes to find one of his hiding places. He won’t reappear until the morning. ‘The head of the English Department is a cunt!’ says my father and he smiles benevolently at his own reflection in the dark night of the window. ‘Shut up, darling!’ says Peggy. Her eyes are tightly closed and the inside edges of her lips are stained with wine. ‘I said he is a cunt because he is a cunt. A fascist cunt! I told him so and he didn’t like it!’ Pippa with the red hair laughs and says she didn’t know that cunts had political allegiances, but she doesn’t translate the conversation to her waiting husband. Everyone else stays silent. ‘My wife is a lesbian!’ says my father and he begins to cry. Peggy makes tut-tut noises and asks me to help her clear the table. ‘I don’t love him, I love you!’ she says once we are in the kitchen dealing with a heap of plates. She grabs hold of my arm and squeezes it and her eyelids flicker. ‘I didn’t marry him for this!’ she says. Next door, my father is making loud clock noises, to show that he is bored. ‘Tick-tock, tick-tock, tick-tock.’ Then he yawns very loudly. ‘You’re all hypocritical shits!’ he says to his guests. I return to the table with Peggy. We are both smoking. My father snatches the cigarette from my mouth and stubs it in the ashtray. Peggy picks it up and lights it and pushes it back between my lips. ‘Let her smoke, damn you!’ she says and she smiles at the guests.

Copyright © 2008 by Julia Blackburn. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.