Chinatown (1974)

Tell me the story again, please.

Very well, there was this detective in Los Angeles, Jake Gittes, as honest as he could be after years with the LAPD. But he had had trouble in Chinatown and so retired into independent operation. Then he was set up, and you have to realize that he was sought out in just the way that Scottie was in

Vertigo. Someone picked him to receive the story that Hollis Mulwray was having an affair. Trace it back and you'll see it was all a cruel design. Jake Gittes did his best, but he was as much damage as he was good, because he fell in love on the job with a woman who was such trouble it smelled like gangrene. And so, finally, the bad man, Noah Cross, was left in charge, and they led Jake away to some hiding hole and they whispered in his ear that it was all “Chinatown.” I really don't see why you love the story so much.

It was a story that Robert Towne, an Angeleno, dreamed up for his pal Jack Nicholson to play. And another friend, Robert Evans, would produce it at Paramount. But Evans thought that Roman Polanski should direct, and Polanski battled with Towne over the script-it had to be clearer and tougher. Towne had had a gentler ending, with less death. But Polanski knew it was a story that had to end terribly-so no one forgot. The director won, and the picture worked with its very bleak ending.

What's more, the picture worked in every way you could think of. Faye Dunaway was the woman, and she was lovely but flawed and incapable of being trusted. John Huston was Noah Cross, and the more you see the film, the better you know that that casting is crucial, because Cross is so attractive, so winning, so loathsome. And the rest of the cast was a treat: Perry Lopez, John Hillerman, Darrell Zwerling, Diane Ladd, Roy Jenson, Burt Young, Belinda Palmer, and the others. John Alonso shot it. Richard Sylbert was the production designer. Sam O'Steen edited the film. Jerry Goldsmith delivered a great score. The craft work, the details, are things to dream on. We are in 1937. And don't forget Polanski's own little bit of being himself.

So it's a perfect thriller, and a beautiful film noir in color. Moreover, if you care to look into how William Mulholland once brought the water from the Owens Valley to Los Angeles, it is a piece of local history. But with this extra aspect-that accommodation of the history of southern California itself, and the fable of how sometimes power and corruption make life and the future possible- you also get another reflection on filmmaking in that world: It is that you can do very good work, work so full of affection and detail and invention that you can live with it over the years, but in the end the system will fuck you over and someone will whisper in your ear that you are not to mind, because “It's Chinatown.”

And that's how it worked out. There had been a trilogy in the reasonably honest mind of Robert Towne. They let him make the first part near enough to his own dream so that he would always know it could have been. And then they crushed him on the second (

The Two Jakes)-blew it straight to hell-so no one had the heart ever to ask about the third.

Duck Soup (1933)

Duck Soup is all credentials: Leo McCarey directed; Herman J. Mankiewicz produced it; Bert Kalmar and Harry Ruby wrote it; Ansel Adams photographed it, mostly at magic hour; it was Marcel Proust's favorite Marx Brothers film; the Duke of Windsor watched it constantly in his years of exile. Are you believing this? Where does that get you? It was the poorest performer of all their Paramount films-there was a time when the University of Chicago economics department was stocked with people who'd done their Ph.D. on “

Duck Soup and the Collapsing Cash Nexus” and similar titles. In other words, how could you expect a dazed, defeated, demoralized, and de-walleted population to go to see a film that mocked government when the folks were waiting for a New Deal?

In case you can't place the film, this is the one where Mrs. Teasdale (Margaret Dumont) will give the nation of Freedonia $20 million if Rufus T. Firefly is appointed its leader (and if she gets the fire in the fly). Aha, you may say, such cynicism and manipulation the affairs of modest third-world nations was far more likely the cause of public despair. Enter Trentino (played by that very respectable actor Louis Calhern), the ambassador from Sylvania (before it was in the TV business), and soon we are on the brink of world war. But why remind the public of that?

Like many Marx Brothers films,

Duck Soup has the suspicious air of a few set pieces strung together with Christmas lights and Hollywood was learning with talk and plots and so forth that the manufacture of whole films (as opposed to scene anthologies) was a dirty job, even if you were being paid for it. There has never been a better answer to the question of what holds this film together than glue. The essential ethos of the Marx Brothers (this is Irving Thalberg talking as he prepared to ship them off to Culver City) is to make their fragmentation seem natural. So Thalberg foresaw Marxian nights with a film program continually interrupted by little scenes from Marxist groups. This was a principle applied fully on the BBC years later with the arrival of Monty Python. The show might be over, but still somehow the other programs-the news, Gardeners' Question Time, England v. Pakistan-could not but take on a Pythonesque flourish. This could have revolutionized TV, but the Python boys (who had been to university) asked for ghostly residuals.

Anyway,

Duck Soup has the extended routine where Chico (as Chicolini) and Harpo (as Pinky) harrass Edgar Kennedy. And it also has Groucho and the mirror, which is enough to persuade you all to get every bit of polished glass out of the house.

If you find you like this sort of thing, you'll be glad to know that

The Cocoanuts, Animal Crackers, Monkey Business, and

Horse Feathers once existed. There was a moment-we call it sound-when the Marx Brothers made the trip from vaudeville to Hollywood, and it's like Neil Armstrong stepping down onto the moon and landing on a banana peel.

Seven Samurai (1954)

In sixteenth-century Japan, an idyllic village, in a valley below steep mountains, discovers that bandits will attack as soon as the barley crop is ripe. They have suffered before-should they yield again, or fight back? A small committee is appointed to find samurai who will defend the village. This is a long film, drawn out by a master of suspense and control (over 200 minutes in its full version). We meet the seven samurai. We see them living in the village, doing their best to train the farmers and work out a strategy. And then there is battle, begun in sunlight and ending in pouring rain. Why seven?

The film is over fifty years old now, and it is impossible for anyone to see it today without thinking of the traditions it inspired: not just

The Magnificent Seven and the Sergio Leone pictures; not just the immense field of martial-arts films based on the Western fascination with samurai armor and Japanese discipline; not just Melville's

Le Samourai, or Frankenheimer's

Ronin, but the laser-beam sword battles of the

Star Wars series. (George Lucas was a huge admirer of Akira Kurosawa-and the eventual coproducer on

Kagemusha.)

Yet I urge you to do your best to regard this film with the eyes of 1954, and to see the astonishing vigor from Kurosawa that goes into every frame and meeting. I suspect that by the time he made

Seven Samurai, he was well aware of and much in love with tropes from the American Western. But then consider the things that are uniquely his: the restless camera movements, the urge like that of a mettlesome horse, to be galloping and moving; the intense, burning close-ups and the way in which the cadet samurai can look at the weary master and say, “You are simply great!,” and we feel the justice of it, but understand the sad smile on the master's face. There are the lovers on the forest floor, spread-eagled and surrounded by wildflowers. There is the terrible look on the face of the kidnapped wife as she realizes her husband is about to rescue her. There is the sudden use of slow motion (so that you wonder if you really saw it). And the sounds of running water, of bird cries, of the wind and of Toshiro Mifune's snorts of derision for everyone- himself included. These images and sounds are like moments in Shakespeare.

You can say that the film was a canny attempt to win Western audiences-and it undoubtedly achieved that. But over fifty years later, you can marvel at the rich black-and- white, the natural sounds, the drumbeats, the hooves on the ground and the music. It is a landmark in action films, but in its treatment of heroism, too. These samurai work and some of them die, for mere food. You wonder if they may seize the village, or be turned on by the villagers, for there is not too much trust between those parties. But the integrity of the contract prevails. There has always been a vein of cinema in which people do the right thing. And

Seven Samurai comes as that notion was being treated with cynicism. But there is no denying or forgetting the faces of these men. They are the seven samurai, and they have found themselves. They do not need to say so, because we understand it.

The Sign of the Cross (1932)

“Bib-lit” is mercifully light on the ground these days, but in a world afflicted by bank closures and food lines, thoughts of sin and the sinning class could be stirred. No one had more history in this than Cecil B. DeMille, and as it turned out

The Sign of the Cross is one of the more intriguing social commentaries of 1932, even if one is not quite sure whether it is a Marx Brothers film or not. No, it can't be-it moves too slowly.

There was a play, by Wilson Barrett, which seems to owe a few centavos to Henryk Sienkiwicz's

Quo Vadis? in that it involves Christians, lions, and Nero. Waldemar Young and Sidney Buchman shrugged off whole libraries of “research” to come up with a script in which a noble Roman, actually named Marcus Superbus (Fredric March) falls for a coy handmaiden (Elissa Landi), and thereby rejects the sinuous offerings of the Empress Poppaea (Claudette Colbert), whose sexual energies are not exactly fulfilled by Nero (Charles Laughton).

This is the one where Colbert takes a bath in asses' milk. The man who handled that scene was DeMille's top designer and costumer, Mitchell Leisen. DeMille wanted an effect whereby Ms. Colbert's nipples might fleetingly appear, like bubbles, above the milk. So Leisen and the actress had a lot of fun measuring and pouring, while DeMille- apparently-was in the wings trying to get a glimpse. Colbert takes her bath like a good sport, and it's apparent that she's wearing nothing. But then, under the lights of Karl Struss, the bath began to demonstrate the fermentation process that makes cheese. The story is that Leisen and Colbert went out to dinner, and while they were out the milk hardened so that a visitor to the set thought it was marble, fell in, and was only just saved. You don't have to believe all this, but the surge in yogurt sales in Los Angeles plainly dates from this period.

What you cannot avoid believing-because it's there onscreen-is the unbridled way in which Laughton seems to say to Colbert, “Well, if you're the empress, I'm the queen!” In other words, he gives what is the most flagrant and fleshy portrait of an abandoned homosexual spirit seen in an American film until that time. DeMille was said to be unsure of what was happening. He tried to direct Laughton, but it was impossible. And at the end of it all, when DeMille asked Laughton whom he wanted to play next, Laughton answered, “You!”

Rome burns, Nero plays the harp. Christians are gnawed by lions-Leisen said they used prime rack of lamb to get the lions interested. (Otherwise, Leisen said, they were inclined to chat about the last film they'd made.) DeMille reissued the film in 1944, with fresh scenes and a prologue written by Dudley Nichols. Apparently he had had a vision that the Nazis were like Nero. It is a business terribly vulnerable to visionaries. But Nero and Poppaea are more than they seem: They are the first onscreen portrait of the Hollywood marriage where he's gay and she's viciously carnal because of it. And you can still see that today.

To Be or Not To Be (1942)

The point may be obvious. It may gloss over fine issues of taste. But in some total conflict, if one side is making

To Be or Not To Be in the middle of a war and the other is not-you know which side to root for. No, there are no Nazi equivalents to this film, no film in which the Goethe Institute, let's say, sends a Schubert lieder singer on a tour of the United States and she tries to conduct an affair with a spokesman for the Bund. (You're tempted by the sound of it? But only because you've grown up in a culture addicted to irony, sarcasm, self- effacement, and that essential ingredient of American acting once identified by Kenneth Tynan-its Jewishness.)

It has to be said that Samson Raphaelson- Lubitsch's preferred writer-chose to be unavailable for this project, because he feared that it would end in charges of bad taste. So Melchior Lengyel shaped the idea and Edwin Justus Mayer wrote the script about a Polish acting company in Nazi-occupied Warsaw that has a hard time doing

Hamlet, but which gets drawn into a masquerade against the Nazis that may help win the war. This is the company led by Maria and Joseph Tura (Carole Lombard and Jack Benny), when he is doing

Hamlet and she has a Polish flier after her and she tells the boy to rendezvous in her dressing room just after her husband begins the speech “To be or not to be . . .”

What follows is nothing less than a farce in which the Nazis are the butt of the humor, but in which “So, they call me concentration camp Erhard, do they?” is relied upon to get repeated belly laughs. Some find it too much. I suggest that its brilliance lies in the concentration on actors at the heart of the story and the casting genius that saw how far the already wounded face of Jack Benny could consider no greater crime against humanity than walking out on his big speech. And then there is Carole Lombard, ravishing, sexy, happy, and glorious in her gowns. She was dead shortly after the film finished shooting, and it may be that that took away from audience numbers as much as any question of taste.

Alexander Korda was a coproducer on the venture and Vincent Korda did the sets. Those gowns are by Irene, and Rudolph Maté did the photography. The faultless cast also includes Robert Stack, Felix Bressart, Lionel Atwill, Stanley Ridges, Sig Ruman, and Charles Halton. Of course, it is an artifice, protected from the real horror of war. But it has moments when to see the Turas-vain, self-centered, essentially small-minded- is still to recognize how far cinema and egalitarianism can amount to models of ordinary decency. The American cinema has made few lastingly useful political statements, and it has often taken fright at the risk of trying.

To Be or Not To Be is the sort of film that would have earned murder gangs if the other side had won. It is still brave, and it still bespeaks a wholesome insolence in many Americans toward tyranny and the way of life ready to rationalize the death of flirtation.

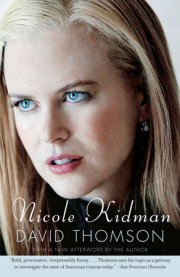

To Die For (1995)

In Little Hope, New Hampshire, and yet from the eternity of TV fame, too, Suzanne Stone turns to us-direct to camera-the freshest sundae, all pinks, creams, blondes, and custards, and goes into the lovely ad lib confession on what she did to her husband, when any idiot can see that why she did it was, quite simply, to be a sundae show on TV, to be not just the weather center in Little Hope, but the Whether Center in America (the question being whether Suzanne is just guilty or delicious-her show is called

Your Guilty Pleasures, in which on reality TV you get to go through with the deepest, darkest longings you've ever had).

Well, no, the glorious

To Die For doesn't quite reach that far. It stays in Little Hope with those grungy kids when its own great vaulting esprit indicates the chance that Suzanne could GO ALL THE WAY-she could be

Up Close & Personal, she could be a Katie Couric, so wide-eyed and pretty that she can take in all of America in what amounts to the first TV blow job.

It's a brilliant try, taken from a dark, witty novel (based on a real case) by Joyce Maynard and very well scripted by Buck Henry, even if it falls short of some final manic, cartoon surge where one murder makes Suzanne a killer hit. It needs the zest of

Network, that satirical energy, and the understanding that Suzanne Stone really is modern America- pretty, sweet, shallow, and a killer-diller.

It may be that Gus Van Sant was not quite the director for that kind of satire. He seems as interested in Joaquin Phoenix as he is in Nicole Kidman, and that's understandable at the New Hampshire level, because Phoenix is outstanding and very accurately observed. But Nicole-in claiming her own identity and naughty-flirty presence on our screen-was reaching for the stars, not just the George Segal figure, but the Robert Redford stiff from

Up Close & Personal and a kind of Clintonian president who sees her and sighs, “Santa Monica!”

So the parents are cameo treasures, but the film lingers with them too long. And really Matt Dillon needs to be disposed of more quickly. Suzanne is the Bad Seed grown up, and Nicole is like a candy rocket willing to soar over the mediascape, shedding light and her panties wherever she goes. A masterpiece was in prospect-instead we have a very nice, tart, daring comedy and the sublime insight that so long as Suzanne is confiding in

us, direct to camera, mouth to mouth, she can get away with anything.

So this was Nicole Kidman's real debut, yet look how far the business held back from putting her in more outrageous comedies, let alone pictures in which she rose like bubbles in champagne to the level of mass murder. Here is a unique sensibility, seductive and devouring, and all too often Ms. Kidman would be fobbed off with earnestness or cuteness. Terrific support from Illeana Douglas, Maria Tucci, Casey Affleck, Alison Folland, Dan Hedaya, and David Cronenberg.

To Have and Have Not (1944)

Published in 1937,

To Have and Have Not is the closest Ernest Hemingway ever came to a political novel. Harry Morgan dies at the end with the gasping cry, “One man alone ain't got a chance.” But in the Howard Hawks film, seven years later, a man alone-call him Harry Morgan-while he claims to be hard up, seems to be dressed by the J. Peterman catalogue; he has a boat and a sidekick named Eddie; he is insouciant about the war and taking any stance toward it; and he gets this odd girl, or “look,” prepared to teach him to whistle. So

To Have and Have Not is the Warner Brothers wartime movie in which Humphrey Bogart stays “above” the war.

There's more to it than that, but don't overlook the breathtaking charm of Hawks electing a story which has some nasty signs of Gestapo-tainted Vichy and still disdaining the war. So Harry Morgan is a relic from a sweeter past, hiring his boat out to ugly American fishermen, and getting along. At the hotel, the owner (Marcel Dalio) would like him to help some Resistance people- but resistance to what? Meanwhile, Harry has “her” on his hands, lolling in his doorway, and tossing insolent remarks at him along with boxes of matches and looks that might burn a man's toupee off him.

Hawks asked Jules Furthman to do a screenplay, and apparently let William Faulkner doodle a few scenes. It would all put Papa in his place. And then one day, Slim Hawks passed a fashion magazine over to Hawks, and there she was, Betty Perske, in a pretty hat, standing outside a Red Cross office, like a vampire. She was eighteen or so, and her voice was deep already. Hawks got Betty to wear “Slimmish” clothes. He took her voice lower. And he told Bogart that it would be a kind of love story if the girl kept topping him with insolent lines.

Bogart said that sounded fine, but he was overoccupied with his raucous wife, Mayo Methot, and Hawks had every reason to think that “Lauren Bacall” would be not just his contract property, but a new Slim, a bit slimmer and nineteen. Alas for lecherous dreams (and don't knock them as a major inspiration for good movies). Bacall had a soft heart- Howard always assumed that all the girls he discovered were as cool as he was. She fell in love with the actor, the drunk, and the toupee!

Meanwhile, it's a screwball classic posing as a war movie, with a little bit of musical as Hoagy Carmichael teaches Bacall to sing. Sid Hickox got the sultry Caribbean look. Charles Novi did the shabby sets. Max Steiner scored it, and Carmichael and Johnny Mercer did the songs. Effortless, serene, grown-up and childish at the same time. Is there a more “Hollywood” movie? Also with Dolores Moran, Sheldon Leonard, Walter Molnar, Walter Sande, and Dan Seymour. You kept the title? said Hemingway, perplexed. Sure, said Hawks-I had this girl and then I didn't have her. War is hell, Papa should murmur. But nothing's perfect.

Copyright © 2008 by David Thomson. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.