Chapter 1The newsboys of New York could hardly wait for February 12 in 1908. It may have been just another Wednesday to some people, but not to the urchins and orphans who swarmed over the sidewalks every morning to hawk the

World or the

Sun, the

Herald, the

Tribune, or the

Times, fanning out again in the afternoon to sell the

Press, the

Telegram, the

Globe,

Mail, and

Evening World. In the days before broadcasting, the news of the world didn’t move any faster than the sweaty little boys who carried it—but they didn’t waste a second. They couldn’t. A big city had a couple of dozen newspapers in 1908. And what is more, the leading papers issued four or five editions per day. It was a daily deluge that made newsboys run as fast as they could with each succeeding bundle of papers, getting rid of the old news just before the new news came along.

When the day finally came to a close, New York City’s orphan newsboys could look forward to decent surroundings at the Newsboys’ Lodging House on Chambers Street in Lower Manhattan. On February 12 in 1908 about three hundred of them were also looking forward to a special feast for Lincoln’s Birthday: turkey, cranberry sauce, celery, potatoes, turnips, pie, and coffee, all courtesy of a patron named Delano Weekes.

Robert T. Lincoln, the son of the sixteenth president, was on the list of guests invited to share the newsboys’ bounty. As a resident of Chicago, he’d already sent his regrets, though. So had another Union leader’s son—one with a less convincing excuse. George B. McClellan, namesake of Lincoln’s early favorite among Yankee generals, was the mayor of New York City in 1908. Bookish and a little vague under the best of circumstances, McClellan had a long list of appearances to make on Lincoln’s Birthday, and he sent word in advance that Chambers Street wasn’t among them.

In the early morning, while the newsies were bleating for business and wondering just exactly what kind of pie they’d be having later on for dessert, the next round of headlines was sprouting all around them. In Brooklyn, a twenty-eight-year-old tailor from Italy lay dying; he had been shot five times by the mafia, which was surging to new heights of influence in 1908, dumbfounding even hardened Americans with its capacity for violence. “The Black Hand wrote to me demanding money,” the tailor was telling police early that morning from his deathbed, “and I refused. Last night, they sent two men after me. They got me.”

He wasn’t the only one in trouble. The organizers of the Grande Redoute Rose—the Pink Ball—were under siege from all of the women on the guest list who didn’t happen to own a pink gown, and who couldn’t get one in time for the February 14 dance. The committee spent the morning debating whether or not to allow white.

No one in New York, however, or anywhere else, had a worse day than John J. Grant, a printer by trade. He swallowed poison, slit his wrists, and then jumped off the Brooklyn Bridge—and lived. As soon as he was rescued, he was arrested.

Because schools, government offices, brokerages, and other businesses were closed for Lincoln’s Birthday, the stores were crowded right from the start. Macy’s celebrated its fiftieth anniversary by putting nearly everything on sale, selling eight-rib umbrellas for $5.00 each. Anyone who bought one could have brought it home in a bag, though; the morning was perfectly clear, with temperatures in the mid-thirties. Automobiles were also on sale in mid-February. “This is bargain time,” confided one agency in boldface type in the newspaper. Those who believed it could visit the showroom on Broadway north of Times Square, the same neighborhood in which most of New York’s car dealerships were located.

The Broadway Mammoth Automobile Exchange, on Fifty-sixth Street near Broadway, about ten blocks up from Times Square, declared in its own ad that “Swell rich man’s cars can now be bought cheaper than inferior new ones.” Since swell rich men at the time were paying between $6,000 and $12,000, equivalent to about $150,000 to $300,000 today, there was some incentive to look for an overlay. “Pierce-Arrow, $850,” advertised Broadway Mammoth. “Thomases, all models, 1905, 1906, 1907, $600 to $1,500.” One reason for the drastic depreciation in price was that a car in those days didn’t have a long life on the road; after about ten thousand miles, a customer was presumed to have had his or her money’s worth. But then, it would take the average customer three years to log as many as ten thousand miles in 1908.

In practical terms, the typical secondhand Thomas in the Broadway Mammoth lot had progressed a mere seven blocks, since the Thomas Agency, where the new cars were sold, occupied a building on Broadway at Sixty-third Street. A New Yorker out walking on the brisk morning of the twelfth couldn’t fail to notice the Thomas Agency. Nearly every inch of its four-story facade was draped in decoration, with banners at every window. Something special was in the air—along with the flapping of a great many flags. All down Broadway, the buildings were decked out in colors and patriotic signs. Lew Dockstader, a popular comedian, was inspired by the display to assume the persona of Abraham Lincoln taking a walk in New York: “I was much surprised as well as gratified when I arrived in New York,” he said, “to find myself so well-heralded. I walked up Broadway, and flying from many hotel fronts I noticed bunting and flags telling the glad news that I was here.” But then Dockstader’s Mr. Lincoln finished by adding, in a rather perplexed way, “Someone just told me that the decorations were not for me—but for a car race.”

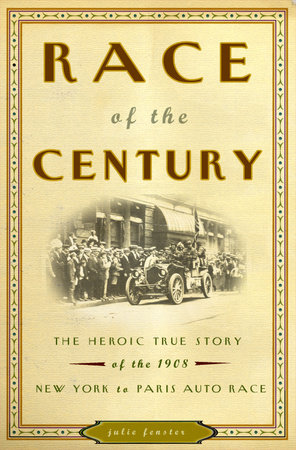

The crowds gathering on Broadway all morning were not out to honor Abe Lincoln, either. They were on the avenue to catch sight of the start of the New York-to-Paris Automobile Race. There would only be one—one race round the world, one start, and one particular way that, for the people who lived through it, the world would never be the same. The automobile was about to take it all on: not just Broadway, but the farthest reaches to which it could lead. On that absurdity, the auto was about to come of age.

“By ten o’clock,” reported the Tribune, “Broadway up to the northernmost reaches of Harlem looked as though everybody was expecting the circus to come to town.” The excitement was generated by the potential of the auto to overcome the three challenges most frustrating to the twentieth century: distance, nature, and technology. First, distance: in the form of twenty-two thousand miles of the Northern Hemisphere, from New York west to Paris. Second, nature: in seasons at their most unyielding. And third, the very machinery itself, which would be pressed hard by the race to defeat itself. Barely twenty years old as a contraption and only ten as a practical conveyance, the automobile couldn’t reasonably be expected to be ready to take on the world. But there were men who were ready and that was what mattered.

The six cars entered in the race were parked in Times Square, facing out of the wide end of the triangle formed by Forty-third Street, Seventh Avenue, and Broadway (which slashes diagonally across Seventh Avenue). For the moment, the cars were separated from the rest of the world by a crowd of a thousand people, who not only wanted to see the start, but touch it. After nine o’clock, another thousand or more pressed into Times Square every five minutes.

“The crowd was one of the worst that the police have had to handle in years,” reported the Globe. “It was one black mass.” Three hundred policemen were on hand all morning, charged mainly with keeping a one-lane road open along the route laid out for the cars. If the crowd had its way, after all, the cars would never budge. When a gaggle of women waiting in front of the Cadillac Hotel on Broadway at Forty-third Street grew too merry and spilled over the curb, a detachment of mounted police arrived in seconds to herd them back.

Times Square wasn’t yet a theater district in 1908, but a neighborhood of hotels, watched over by the New York Times Building, the lone skyscraper in the middle of it all, and the source of its name. Ultimately, the race was to head north out of the city. But for the six racecars facing the Times Building across Forty-third Street, the route started south on Broadway for a block, making a turn around the base of the square, before heading north up Seventh Avenue to the intersection at Forty-fifth Street where crooked Broadway barged into Times Square. The cars would then follow Broadway out of the city.

In the square, the north-south avenues were lined by a double row of cars, two hundred of them in all colors and sizes. Their owners had received special permission to accompany the racers at the start, and for that purpose each had been assigned an immensely valuable parking space well in advance. Once the six racers started moving, the enthusiasts were to peel away from the curb in their autos and join the convoy.

By 10:30, the crowd surrounding the racecars numbered fifty thousand. In photographs taken from high up in the Times Building, the scene looked as though a blanket had been spread over the square, a blanket made up of black overcoats. Faces popped up out of the black, looking every which way to see something of the cars or the spectacle they had created. Even those people who couldn’t see the racers at the starting line could smell gasoline. All the while, the music of a brass band filled the air.

Celebrities had a special place, as they always do in New York. A grandstand had been erected directly across Forty-third Street from the cars, so that those on it would have a view both of the start and of the cars as they made their way up Seventh Avenue, after the initial lap of the square. In the meantime, the celebrities could see the cars, and the crowd could see the celebrities. Colgate Hoyt was bustling back and forth on the grandstand, a solidly built man recognizable by his thick moustache and the thin hairline just then disappearing over the horizon of his head. Originally from Cleveland, Hoyt specialized in railroad finance—and good connections. His wife, Lida, was a niece of General William T. Sherman, and he counted John Rockefeller and steel magnate Charles Schwab among his closest friends. Robust by nature, Hoyt was on the board of directors of the Aero Club of America, a group dedicated to the airplane, which had been invented only five years before. The club was so riddled with infighting that a wit of the day credited it with originating aerial warfare. At the time of the race, Hoyt was also president of the Automobile Club of America, and that gave him a place on the grandstand.

Jefferson DeMont Thompson was there, too. A developer and landlord, Thompson was not as rich as Hoyt, but he was likewise interested in airplanes and automobiles and was a member of all the concomitant clubs. Thompson was also in the much more rarified Motor Scooter Club of America, the scooter of 1908 being a vehicle for use on ice whenever people couldn’t toy with their yachts. Thompson served as president of the Broadway Association, which guided the development of the Times Square neighborhood, and so his place on the grandstand was practically deeded.

Keeping to themselves on the grandstand were Miss Theodora Shonts, the most famous young woman in New York in mid-February 1908, and her friends from France, the Duc de Chaulnes, the Duchesse d’Uzes, Prince Galitzine, Baron Louis de Conde, and the Baron de la Boullere. They were not in black overcoats, but in as much fur as they could arrange around themselves. In Paris, the Duc de Chaulnes was known as a penniless boulevardier who was always trying to get himself married to a rich girl. But in New York, he had finally crossed his own finish line. Engaged to the very rich Theodora Shonts, he was the toast of the town, regaled as the veritable heir to the mantle of Charlemagne. Theodora was the most envied woman in the city, standing with her arm draped through that of the duc she’d brought home from Paris. No one knew or cared that the Duc de Chaulnes had owed his tailor $1,345 since 1901. Nor did the throngs pointing out the duc to one another in Times Square know that he had gone on a morphine binge just before leaving Paris—and that, purely for love of Theodora or possibly in fear of her father, he had made it a long, unrestrained bender that lasted for days. With that, he had sworn off drugs forever.

The race was due to begin at 11:00 a.m., when Mayor McClellan was scheduled to fire the starting pistol. As the time drew near, some observers detected a somber atmosphere bestilling the crowd, as bystanders looked at the racers and realized just how treacherous a trip lay in store for them. Everyone couldn’t be contemplative, though. “Send me a cake of ice from Siberia,” shouted one observer. “See you in Paris,” exclaimed another. Not all of the comments were even in English.

Some people were in Times Square to see history—or at least news—in the making; some to join in the celebration of automobile sport. Some were only there to catch sight of the duc and future duchesse. But many of those who cheered loudest were caught in a patriotic fever, brought on by the sight of the German, Italian, or French entries. Or the American one. The New York-to-Paris Race struck them all as a holiday that was set to move west across the world. Excitement would well up wherever the race arrived; a person had only to look up from an average day to see it and hear it and get jostled in the streets by it. That’s what was happening in Times Square on February 12, 1908.

“Undoubtedly the sternest test of men and machines that has ever been undertaken,” reflected an editorial in the

New York Times. “This stupendous undertaking is almost on a par with the dash for the pole,” observed the Baltimore American. “It shows how deeply seated the spirit of adventure and of emulation is in the human race.”

The Denison (Iowa) Bulletin was more practical. “You think that automobile race doesn’t amount to anything?” the editor would write. “Well, now, how much more have you thought about and studied autos the past few weeks than you ever did before? And what you have been doing 50,000,000 other people have been doing also, and of that fifty millions, many have the money to spend for machines of their own. See?”

Copyright © 2005 by Julie Fenster. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.