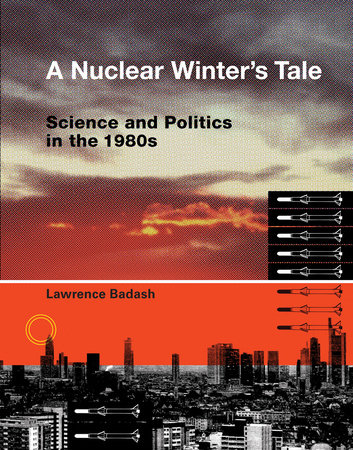

The rise and fall of the concept of nuclear winter, played out in research activity, public relations, and Reagan-era politics.The nuclear winter phenomenon burst upon the public's consciousness in 1983. Added to the horror of a nuclear war's immediate effects was the fear that the smoke from fires ignited by the explosions would block the sun, creating an extended “winter” that might kill more people worldwide than the initial nuclear strikes. In A Nuclear Winter's Tale, Lawrence Badash maps the rise and fall of the science of nuclear winter, examining research activity, the popularization of the concept, and the Reagan-era politics that combined to influence policy and public opinion.

Badash traces the several sciences (including studies of volcanic eruptions, ozone depletion, and dinosaur extinction) that merged to allow computer modeling of nuclear winter and its development as a scientific specialty. He places this in the political context of the Reagan years, discussing congressional interest, media attention, the administration's plans for a research program, and the Defense Department's claims that the arms buildup underway would prevent nuclear war, and thus nuclear winter.

A Nuclear Winter's Tale tells an important story but also provides a useful illustration of the complex relationship between science and society. It examines the behavior of scientists in the public arena and in the scientific community, and raises questions about the problems faced by scientific Cassandras, the implications when scientists go public with worst-case scenarios, and the timing of government reaction to startling scientific findings.