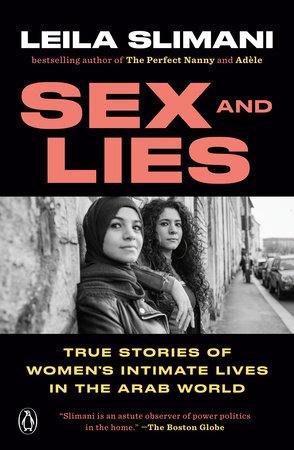

INTRODUCTION

When, in the summer of 2014, I published my first novel, Adèle, some French journalists expressed surprise that a Moroccan woman could write such a book. What they meant by that was an ‘unconstrained book’, a ‘sexy book’, a straight-talking, popular book, the story of a woman suffering from sex addiction. As if, by culture, I should have been more prudish, more reserved. As if I should have made do with writing an erotic novelette with orientalist shades, worthy scion of Scheherazade that I am.

Yet I feel that North Africans are well placed to take on themes relating to sexual suffering, frustration and alienation. The fact of living or having grown up in societies without sexual freedom makes sex a subject of constant obsession. Besides, sex is one issue that’s well represented in contemporary North African writing. It’s there in the autobiographical novels of Mohamed Choukri, in the poetry and novels of Tahar Ben Jelloun, in the novels and criticism of Mohamed Leftah and in the novels and films about gay life of Abdellah Taïa. Erotic, even steamy, literature continues to be reinvented particularly among women, such as Lebanese writer Joumana Haddad and Syrian writer Salwa Al Neimi, whose novel The Proof of the Honey became a bestseller, following in the footsteps of the mysterious Nedjma, eponymous protagonist of the novel by Kateb Yacine.

So my first novel is in no way exceptional. I can even say it’s no accident that I created a character like Adèle – a frustrated woman who lies and leads a double life. She’s a woman eaten by regrets and by her own hypocrisy, a woman who steps out of line yet never experiences pleasure. Adèle is, in a way, a rather extreme metaphor for the sexual experience of young Moroccan women.

When my novel was published, I insisted on doing a book tour around Morocco, to present my book in several of the country’s cities. I visited bookshops, universities and libraries. I accepted invitations from charities and support groups. The two weeks of my tour were a true revelation. I had never doubted the hunger for debate among those I was going to meet, but at every one of my encounters I was struck by how a discussion on the subject of sex enthused people, especially younger people. After the sessions, many, many women came up to me wanting to talk, to tell me their stories. Novels have a magical way of forging a very intimate connection between writers and their readers, of toppling the barriers of shame and mistrust. My hours with those women were very special. And it’s their stories I have tried to give back: the impassioned testimonies of a time and of its suffering.

My intention here is not to document a sociological study nor to write an essay about sex in Morocco. Eminent sociologists and brilliant journalists are already doing this enormously delicate work. What I want is to render these women’s words directly, as they were spoken to me: their intense and resonant speech, the stories that shook me, upset me, that angered and sometimes disgusted me. I want to give these often painful angles on life a platform in a society where many men and women prefer to turn away. By telling me their life stories, by choosing to break taboos, all of these women showed one thing, at least: that their lives matter. They should and do count. By confiding in me, they chose, if only for a few hours, to step out of isolation and to invite other women to realise that they’re not alone. This is what makes their accounts political, committed, liberating. At the time of these encounters, I often returned to Moroccan sociologist Fatima Mernissi’s remarks about Scheherazade – a superb figure but also, at times, a burdensome precedent for Muslim women: ‘She would cure the troubled King’s soul simply by talking to him about things that had happened to others . . . She would help him see his prison, his obsessive hatred of women.’* If, for Mernissi, Scheherazade appears a magnificent character, this isn’t because she embodies the sensual and seductive oriental woman. On the contrary: it is because she reclaims her right to tell her own tale that she becomes not merely the object but the subject of the story. Women must rediscover ways of imposing their presence in a culture that remains hostage to religious and patriarchal authority. By speaking up, by telling their stories, women employ one of their most potent weapons against widespread hate and hypocrisy: words.

It’s important to recognise quite how brave the women who speak out in this book have been, quite how difficult it is, in a country like Morocco, to step out of line, to embrace behaviour that is considered unconventional. Moroccan society relies entirely on the notion of community dependence. And the community is considered by its members as both inevitable, a fate they cannot dodge, and a piece of good fortune, since they can always count on it for a kind of group solidarity. So our relationship to our community remains profoundly ambivalent. Another cornerstone of Moroccan society is the concept of hshouma, which translates as ‘shame’ or ‘embarrassment’, and which is inculcated in every one of us from birth. To be well brought up, an obedient child, a good citizen, also means being alive to shame and regularly to demonstrate modesty and restraint. ‘Harmony exists when each group respects the prescribed limits of the other; trespassing leads only to sorrow and unhappiness,’ Mernissi wrote. The price of transgression is very high and anyone guilty of crossing the hudud – the ‘sacred boundaries’ – is punished accordingly and summarily rejected. The women who spoke to me have experienced only what befalls most Moroccans: an appalling, devastating inner conflict between the urge to shake off the tyranny of the community and the fear that freedom would bring all the traditional architecture of their world crashing down. All of them, as you will see, reveal ambivalence from time to time; they contradict themselves, claim their freedom then lower their eyes. They are trying to survive.

Copyright © 2020 by Leila Slimani. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.