PREFACE

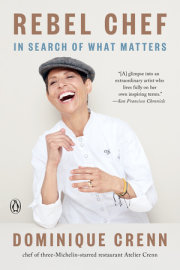

“We three” and Bonza the dog; it annoyed my mother that in the only photo of her and her parents in existence, you couldn't see her face.

MY GRANDMOTHER THOUGHT she was marrying someone vibrant and exciting, a man with wavy hair and tremendous energy. He was a talented carpenter, a talented artist, a convicted murderer, and a very bad poet. He spent his working life as an engine driver and down the gold mines, and when he met my grandmother, sometime in the early 1930s, he was probably employed at the railway station she passed through en route to her office training course.

My mother said two things about this man: that he was “very clever” and that he was “very peculiar.” She also said he had a faulty sense of humor—he liked slapstick—which was her backhanded way of calling him Afrikaans. I gather he was vain about his European origins.

At the time my grandparents met, my grandmother was being courted by someone else, a man called Trevor, or “Bessie Everett’s brother Trevor” as the family on that side remembers him, which is to say, as a known quantity. Nice Trevor, boring Trevor; I picture him in a cardigan, smoking a pipe and reading the less-interesting bits of the daily newspaper. By all accounts, my grandmother and Trevor stepped out only a few times. The fact he still rates a mention, some seventy years on, is because in the story that follows Trevor became the shining symbol of what might have been.

She was called Sarah Doubell, and, like everyone who dies young, is supposed to have been beautiful. She had long dark hair, pale skin, big brown eyes, and slender ankles. She would get “stopped on buses,” said her older sister Kathy, and asked out by men of superior backgrounds. Before they moved to the coast, her family had been skilled laborers on the ostrich farms, and in group photos, where her siblings look solid, agrarian folk in stout boots and triangular smocks, Sarah seems always to be in floaty dresses and unsuitable footwear. She didn’t marry Trevor. She married the other man, at the Babanango Court House, in the presence of her sister Johanna and her brother-in-law Charlie, and moved to a cinder-block house somewhere out in the country. They came into town for the birth of the baby.

There is a single photo of that brief family, sitting on a picnic mat outside in the sun, the father in a shirt and tie, the mother in a pretty dress, and the baby in a bonnet looking up at her father. A bulldog pants in the foreground. “‘We Three’ and Bonza,” Sarah has written on the back, the “We Three” in quotation marks, as if she is poking affectionate fun at them, a conspiracy of happiness against the rest of the world. I assume they were happy and that my grandmother didn’t know about her husband’s murder conviction. Which is a shame. It would have been useful information to have had when, as she lay dying, she was deciding with whom to leave my two-year-old mother.

For a few years after her death, Sarah’s family stayed in touch with the husband. They were relieved to hear he’d remarried. And then one day he was gone. It was almost forty years before the family tracked down the baby, by which time she was living in London and married to my dad. Her cousin Gloria, Kathy’s daughter, sent her a letter introducing herself as a member of her mother’s family and asking where she had been all those years. I wonder now how my mother replied.

• • •

MY MOTHER DIDN’T TALK much about her past when I was growing up. I knew she had emigrated to England from South Africa in 1960 and, in the intervening years, had been back twice. I had met none of her seven siblings and could name probably half of my sixteen first cousins. There were a few stories: about her childhood, her work, her friends, which for the most part she made sound fun. She also hinted at another history, behind the official version, which sounded less fun and which for a long time I was happy to ignore. It was only when she was dying that she told me anything specific. When she was in her mid-twenties, she said, she’d had her father arrested. There had been a highly publicized court case, during which he had defended himself, cross-examining his own children in the witness box and destroying them one by one. Her stepmother had covered for him. He had been found not guilty.

I was calm as she told me this, as I had not been on the one previous occasion she had tried to bring it up. Along with everything else going on, I filed it away to think about later, but as tends to happen, later came sooner than expected.

Six months after my mother’s death, I flew from London to Johannesburg to try to piece together the missing portions of her life. It is a virtue, we are told, to face things, although given the choice I would go for denial every time—if denying a thing meant not knowing it. But the choice, it turns out, is not between knowing a thing and not knowing it, but between knowing and half knowing it, which is no choice at all.

Even after I discovered the real story, I was still evasive about it, to myself and others. When someone suggested, during the course of writing this book, that I read the “clinical literature,” I was outraged. I didn’t want my mother reduced to the level of case study. I didn’t want to lump her in with all those terrible people moaning on about themselves, going on talk shows to weep and wail. I objected to the language they used: “survivors,” as they sometimes called themselves, seemed to me to be a term that only underlined their victimhood. The notion of “survivordom” had, in any case, become so prized in the culture, so absolving of all behavior resulting from the initial trauma—so completely, narcissistically inviting—that those without very much to survive these days rummage around until they come up with something.

“Hard-hearted Hannah” my mother sometimes called me. Mimics frequently get the style but not the heart of a performance right.

Above all, I didn’t want to give up the memory I had of her and replace it with something skewed and pathologized. My greatest fear, when I started this, was that I would undo all her good work. Finally, one day, during the endless displacement activities one undertakes while writing a book, I bought a research paper online. It was a study by Canadian psychologists into the parenting deficits of women with “girl children” who in their own childhoods had been the victims of extreme sexual and physical violence. There were the well-known repeated behavioral patterns. There were high instances of alcohol and drug dependency. It was the interviews with women who had not gone on to abuse their own children that shook me the most, however. Excerpts from these women’s interviews catalogued the worry they had about overprotecting their children. They saw danger everywhere; they talked about the suspicion of every male who came into contact with their daughters, including their husbands, and the strain this put on their relationships. They talked about the intense pressure they felt to control the environment around their children and of the need to make their children invincible. In the most heartbreaking terms, they talked about the desire to keep them safe without making them crazy. Meanwhile, they had no way of helping themselves.

My mother wasn’t a great one for asking for help. She would rather do something herself than have someone else do it for her. Toward the end of her life, she reluctantly accepted she might need some practical assistance, without ever quite relinquishing the upper hand. When a nurse came from the hospice, my mother extracted her life story and started ringing rental agents on her behalf. When neighbors came around with soup and fans, she smiled as if doing them a favor.

An enormous effort went into maintaining this idea she had of herself, and of me, and there were times when I thought I could see the mechanism at work. It had a hint of the burlesque about it, all her positive thinking. As a child, it annoyed me. “OK, OK,” I thought, “I get it.” Her genius as a parent, of course, was that I didn’t get it at all. If the landscape that eventually emerged can be visualized as the bleakest thing I know—a British beach in winter—she stood around me like a windbreak so that all I saw was colors.

A therapist once described my mother’s background in relation to my own as the elephant in the room, a characterization I reacted strongly against at the time. And my dad did too, when I told him. I have no idea what my mother did with the elephant, but most of the time it wasn’t in the room with us. And so, while I strain to find an explanation for just how a person can live one kind of life to the age of almost thirty and then, witness-protection-like, cut that life off and begin again, I have no real answer. Friendship helped. And humor. Beyond that, all I can say is, it was an effort of will.

She never got any credit for it. Her aim—to protect me from being poisoned by the poison in her system—depended for its success on its invisibility. “One day I will tell you the story of my life,” she said, “and you will be amazed.” She never did, not really, although I think she wanted to. So I went to find out for myself. It’s amazing. Here it is.

Mum, two years old, with her father, Jimmy, in Zululand.

CHAPTER 1

If You Think That’s Aggressive, Then You Really Haven’t Lived

MY MOTHER FIRST TRIED to tell me about her life when I was about ten years old. I was sitting at the table doing homework or a drawing; she was standing at the grill, cooking sausages. Every now and then the fat from the meat would catch and a flame would leap out.

She had been threatening some kind of revelation for years. “One day I will tell you the story of my life,” she said, “and you will be amazed.”

I had looked at her in amazement. The story of her life was she was born, she had me, ten years passed, end of story.

“Tell me now,” I’d said.

“I’ll tell you when you’re older.”

A second later, I’d considered saying, “Am I old enough now?” but the joke hadn’t seemed worth it. Anything constituting a Life Story would deviate from the norm in ways that could only embarrass me.

I knew, of course, that she had come from South Africa and had left behind a large family: seven half-siblings, eight if you included a boy who’d died, ten if you counted the rumor of twins. “You should have been a twin,” said my mother whenever I did something brilliant, like open my mouth or walk across a room. “I hoped you’d be twins, with auburn hair. You could have been. Twins run in the family on both sides.” And, “My stepmother was pregnant with twins, once.” There were no twins among her siblings.

She always referred to her like this, as “my stepmother,” and unlike her siblings, for whom she provided short but vivid character sketches, and even her father, who featured in the odd story, Marjorie was a blank. As for her real mother’s family, all she would say was “Strong women, strong genes,” and give me one of her looks—a cross between Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen and Abandon All Hope Ye Who Enter Here—which shut down the possibility of further discussion.

It wasn’t evident from her accent that she came from elsewhere. In fact, years later, a colleague answering my phone at work said afterward, “Your mother has the poshest voice I’ve ever heard.” I couldn’t hear it, but I could see it written down, in the letters she drafted on the backs of old gas bills. It was there in words like “satisfactory” (great English compliment) and “peculiar” (huge insult). “Diana,” she wrote to her friend Joan in 1997, “such a pretty girl, but such a sad life.” She was imperiously English to her friends and erstwhile family in South Africa, but to me, at home, she was caustic about the English. The worst insult she could muster was “You’re so English.”

I was English. I was more than English, I was from the Home Counties. I played tennis in white clothing. I went to Brownies. I didn’t ride a horse—my mother thought horses an unnecessary complication—but I did everything else commensurate in those parts with being a nice girl. This was important to my mother, although she couldn’t help hinting, now and then, at how tame it all was.

“Call that sun?” she said, when the English sun came out. “Call that rain?” When I got bitten by a red ant on sports day, my mother inspected the dot while I started to sniffle. “For goodness’ sake. All that fuss over such a tiny little thing.” Where she came from, any ant worth its salt would kill you.

Among the crimes of the English: coldness, snobbery, boarding schools, “tradition,” the royals, hypocrisy, fat ankles, waste, and dessert, or “pudding,” as they called it, a word she thought redolent of the entire race. “The English,” she said, “are a people who cook their fruit.” It was her greatest fear that she and my dad would die in a plane crash and I would wind up in boarding school alone, eating stewed prunes and getting more English by the day.

If I’d had my wits about me I might have said, “Oh, right, because white South Africans are so beloved the world over.” But it didn’t occur to me. It didn’t occur to me until an absurdly late stage that we might, in fact, be separate people.

Above all, she said, the English never talked about anything. Not like us. We talked about everything. We talked a blue streak around the things we didn’t talk about.

• • •

MY PARENTS MET at work in the 1960s, at the law firm where my dad was doing his articles and my mum was a bookkeeper. In the late 1970s, when I was a few years old, we moved out of the city to a village an hour away. Ours was the corner house, opposite the tennis club and a five-minute walk from the station.

It was a gentle kind of place, leafy and green, with the customary features of a nice English village: a closely mown cricket pitch, lots of pubs and antiques shops, a war memorial on the high street, and, in the far distance, a line of wooded hills that on autumn days caught the sun and made the village postcard-pretty. It was emphatically not the kind of place where people had Life Stories. Life stages, perhaps, incremental steps through increasingly boring sets of circumstances; for example, we used to live in London and now we lived in Buckinghamshire. It was also very safe. There was no police report in our local newspaper, but if there had been, it would have been full of minor acts of vandalism and dustbins blowing over in high winds. There was the occasional parking violation when the bowls club had a tournament, and two men were arrested, once, for doing something in the public toilets the paper struggled to find words for. “What about the women and children!” thundered a Tory councilor, causing my dad to look up mildly from his newspaper at breakfast. “What has it got to do with the women and children?”

(When my mother read the newspaper, it was with a pen in one hand, so that when she came across a photo of a pompous-looking public official—if he was smiling—she could absentmindedly black out one of his teeth. Helmut Kohl, Francois Mitterrand, Ronald Reagan all lost teeth this way. “Your mother’s been at the newspaper again,” my father would sigh.) She was in many ways a typical resident. She went to yoga in the village hall. She stood in line at the post office. She made friends with the lady on the deli counter in Budgen’s and had a nice relationship with the lovely family that lived next door to us. Their young boys would come around to look at the fish in our pond. Every year I made her a homemade birthday card that depicted scenes from family life. She tacked them up on the kitchen wall, where they faded with each passing summer. I found them recently, seven in all, a memoir of my mother’s existence in the village. There she is, wonkily drawn in her yoga gear, surrounded by me, my dad, two cats, and the fish.

At the same time, it pleased her, I think, to be at a slight angle to the culture; someone who had adopted the role of a Buckinghamshire mum but who had at her disposal various superpowers—powers she had decided, on balance, to keep under her hat. (I used to think this an attitude unique to my mother, until I moved to America and realized it is the standard expat consolation: in my case—a British person in New York—looking around and thinking, “You people have no idea about the true nature of reality when you don’t know what an Eccles cake is or how to get to Watford.”)

In my mother’s case, it was a question of style. She was very much against the English way of disguising one’s intentions. One never knew what they were thinking, she said—or rather, one always knew what they were thinking but they never came out and said it. She loved to tell the story of how, soon after moving in, she was sanding the banisters one day when a man came to the door, canvassing for the Conservatives. “He just ASSUMED,” she raged then and for years afterwards. “He just ASSUMED I WAS TORY.” She wasn’t Tory, but she wasn’t consistently liberal, either. She disapproved of people having children out of wedlock. When a child molester story line surfaced on TV, she would argue for castration, execution, and various other medieval solutions to the problem, while my dad and I sat in uncomfortable silence. She was not, by and large, in favor of silence.

Even her gardening was loud. When my parents bought the house, the garden had been a denuded quarter acre that my mother set about Africanizing. She planted pampas grass and mint. She let the grass grow wild around the swing by the shed. Along the back fence, she put in fast-growing dogwoods.

“It’s to hide your ugly house,” she said sweetly when our other neighbor complained. After that, whenever my mother was out weeding and found a snail, she would lob it, grenadelike, over the fence into the old lady’s salad patch.

“That’s very aggressive,” said my father, who is English and a lawyer. If he ever threw a snail, it would be by accident.

“Ha!” said my mother, and gave him the look: If You Think That’s Aggressive, Then You Really Haven’t Lived.

• • •

WHEN IT WORKS, the only child–parent bond is a singular dynamic. Being an only child is a bit like being Spanish: you have your dinner late, you go to bed late, and, with all the grown-up parties you get dragged to, you wind up eating a lot of hors d’oeuvres. Your parents talk to you as if you were an adult, and when they’re not talking to you, you have no one to talk to. So you listen.

By the time I was eight, I knew that olives stuffed with anchovies were not pukey but “an acquired taste.” I knew that Mr. X who lived down the road was not a blameless old codger but a “mean shit” who didn’t let his wife have the heating on during the day. I knew that Tawny Owl was too scared to drive after dark and that this rendered her useless, not only as a leader within the Girl Guide movement but as a human being generally. Later, I knew which of my friends’ parents had appealed against their children’s twelve-plus results and with what success, and I knew, from a particularly fruitful session at the bathroom door, what my own results were before being officially told. When a classmate was off sick from school for the fourth day running, my mother and I speculated that she and her family were actually in Hawaii, in crisis talks over the marriage. We blamed the dad. “He’s decidedly odd,” said my mother, “don’t you think?”

My mother would never admit to being homesick for South Africa, but she was, occasionally, nostalgic for London. She would, she said, have liked me to have grown up in a more mixed environment. There was only one black person in the village when I was growing up, a man who worked in the library and who was not only black but “gay to boot.”

“Shame,” she said when we passed him in the street. She never lowered her voice when she made these assessments. “Shame,” she would say when she saw someone fat, and smile at them broadly in pity. “It must be glandular.”

“How do you know he’s gay?” I asked. My mother gave me the look: Woman of the World in a Town Full of Hicks.

“It’s the way he walks,” she said. “Among other things.”

• • •

I KNEW A FEW DETAILS from her childhood. My mother loved to tell stories, and there were some dazzling set pieces I begged her to tell me again and again. She had grown up in a series of small towns and remote villages, “out in the bundu” of what was then Zululand, now KwaZulu-Natal, so that most of her stories involved near-deadly encounters with the wildlife and weather. There were hailstones the size of golf balls. There was lightning to strike you dead as you were crossing a field. Those snakes that weren’t hanging from trees waiting to drop down her back were fighting scorpions for the deeds to the toe end of her slippers.

She told me about her auntie Johanna, cracking eggs into a bowl one day and releasing with the final egg a mass of tiny black snakes into the yellow mixture. A cobra had laid its eggs in the henhouse. She told me about her brother Mike and the practical jokes he had played on her. From the earliest age, just as I knew the rules about lying and stealing, I knew what a bad idea it was to leave a dead snake in someone’s bed as a joke, because its partner might come looking for it. Some snakes, she said, mate for life.

As a consequence, if I ever went to Africa, I said, it would be on condition I could wear a balaclava, dungarees, Wellington boots, and some kind of protective headgear. I pictured myself walking down a jungle path dressed in something halfway between a beekeeper’s outfit and what you might wear while welding metal.

“You couldn’t,” she said. “You’d be too hot.”

“I still would, though.”

“It wouldn’t be practical.”

We didn’t go. Instead, every year or so, my dad and I watched as my mother raised the possibility and then talked herself out of it. There were the politics, she said; this was the mid-1980s, when every night on the news we watched footage of government Casspirs going into the townships. There were family politics, too. If we stayed with one, it would upset the others. If we stayed in a hotel, it would upset them all. You have no idea, she said, how a family that size operates.

Anyway, she said, if we went anywhere long-haul, she would rather go to Australia. We didn’t go to Australia. Although the money was there and my dad was willing, I got the impression we didn’t go because, at some level of my mother’s thinking, going to Australia meant flying over Africa. It is quite an achievement, in a village in England, to feel that evasive action is being taken to avoid the southern hemisphere, but that’s how it was.

Instead we went to France and Spain. We went to Cornwall at half-term. I went on school trips to Somerset and to Brownie camp in Liverpool. “I’ll be glad when you’re back,” said my mother, face clenched, seeing me off at the coach. I thought the scene demanded tears and began, experimentally, to sniffle. “For goodness’ sake,” said my mother, relaxing into irritation. “It’s enough now.”

• • •

AMONG HER STORIES, there was one that made me vaguely uncomfortable. I couldn’t put my finger on it at the time, but I see now what it was: the threat of withheld information. It came with one of her looks, the one I didn’t like: a kind of sideways swipe of the eyes, like windows on a desktop hastily minimizing.

After my mother had arrived in England, but before she had met my dad, she had gone to see a healer, a retired postman and “humble little man,” she would say (as if we were royalty), who lived in a council flat in Tottenham. She didn’t believe in all of that; on the other hand, you never know, and so, on the recommendation of a friend whose back he’d fixed, she went to see Mr. Trevor.

His visions came out in flashes over tea. She would have one child, he said, a girl with long fingers like a starfish (true). She would face a fork in the road one day, and depending on which branch she took, be either very happy or slightly less happy (the former, I hope). At some point in the session, Mr. Trevor came over peculiar and in a horrible voice said, “Is that dirt or a birthmark?”

“That was your father,” he said, coming to. Her father was dead and had in any case never been to England. Mr. Trevor couldn’t possibly have delivered his mail.

Whenever she told this story, she would lift her hair and show me, at the nape of her neck, a strawberry-colored birthmark that had survived her father’s best efforts to scrub it off. Those were always the words he would use, she said.

• • •

LETTERS CAME IN from her siblings occasionally; nothing for years and then a fifteen-page blockbuster written entirely in capitals. She would leave it on the kitchen table for me, for when I got home from school. “Read it to me,” she said, and I would.

To me, her siblings had a kind of mythical status, partly for the glamour all large families hold for only children, and partly for their complete and utter absence from our lives. When my mother talked about them, it was as though they were people she had known a long time ago and had been very fond of, once. There was the one she called her best friend. There was one who was her conscience. There were two she hardly knew. There was one who’d died of whooping cough as a child, whose small white coffin she remembered walking behind. There was one who was very charming but whom you had to keep an eye on. There were two she called her babies—“Fay was my baby, Steve was my baby”—whom she’d brought up, more or less, when her stepmother’s hands were full.

There were no photos of these people on display in the house, but she did once dig out a cardboard box from the garage to show me some old sepia-colored photos from an even earlier era. This, she said, was before her mother had died and her father remarried and had so many more children.

There were three or four in the set, small, white-bordered, and faded with age. One was of my mother as a baby, standing in a hot-looking crib, clutching hold of the bars. In another she was standing, waving, in a garden. On the back, my grandmother Sarah had written, “Pauline on her 2nd birthday.” There were two further photos in the set: my mother as a toddler, with fat little legs and scrunched-down socks, standing beside a fresh grave, the soil still exposed; and in the same position on a different day—the grave already looked older. Someone had written on the back, “Pauline arranging flowers on her mother’s grave,” but who that was she had no idea. “Shame,” said my mother, when she showed me the photos, “poor little thing,” as if it were not her we were looking at but someone entirely unrelated to either of us.

Mum putting flowers on her own mother’s grave.

I remember asking her once if we had any heirlooms. It was a word I’d picked up from a friend while tiptoeing around her parents’ formal drawing room one day, where we weren’t allowed to play. My friend had pointed out various spindly legged chairs and silver trinkets that had been her granny’s and which, she said importantly, would be hers one day. I had gone back to my own house and, while my mother considered the question, had looked around for something old to cherish.

“What about this?” I said. It was a green cigar box in thick, heavy glass with a brass hinge.

“For goodness’ sake,” said my mother. She didn’t know where it came from, and anyway, it was hideous.

We didn’t have heirlooms, she said, because she could fit only so much into her trunk, and besides, her mother had died when she was two, what did I want? I was goading her a little, I knew it. Our peculiarities were annoying me that day. Of this particular friend of mine’s mother, my own mother had been known to say, “I don’t know why she’s so pleased with herself. They made their money in gin.”

Actually there were a few things she could have pointed out to me. There was a tiny porcelain teacup, the sole surviving item from a doll’s tea service, with a depiction of the young queen, then Princess Elizabeth, on the side. There was a glass-beaded necklace. And there was a portrait of her mother, Sarah, that hung above the TV in the lounge. It was blown up from a black-and-white photo and painted over in color, in the style of the times. The colors were a little off—the lips too bright, the skin too pale; she looked consumptive, which in fact she was. My mother didn’t mention these items in the talk about heirlooms. They must have struck her as a mean inheritance, the pitiful remains of a long-dead young woman, and when I thought about it later, I was sorry for asking. Later still, I thought about the painting and where she had chosen to hang it; whenever my mother raised her eyes from the TV, she met her own mother’s gaze.

• • •

THERE WAS, IN FACT, something my mother wanted me to have by way of an heirloom. It had come over on the boat with her in an old-fashioned trunk, the kind with its ribs on the outside. “All my worldly goods,” she would say, and when one of these things surfaced in the course of daily life, a moment would be taken, as before an item recovered from Christ’s tomb.

Before I moved countries myself and understood the pull of sentiment over practicality, I thought her packing choices eccentric. So no overcoat, although she was sailing into an English winter, but a six-piece dinner service. The complete works of Jane Austen, minus Mansfield Park. A bespoke two-piece suit in oatmeal with brown trim. A tapestry she had done, even though she wasn’t arty, of a seventeenth-century English drawing-room scene in which someone played the harpsichord and someone else the lute. And at the bottom of her trunk, wrapped in a pair of knickers, her handgun. Getting it through customs undetected was her first triumph in the new country.

The gun was kept in a secret drawer beneath the bookcase in the downstairs guest bedroom, the most secure of the improvised safes in the house. In my parents’ bedroom, a decoy tumble dryer contained some gold and silver necklaces under a pile of citrus-colored T-shirts and a terry-cloth tracksuit whose shade we called aquamarine. Outside the bathroom, in the cavity between two plastic buckets that served as a fortified laundry basket, were my mother’s gold bracelets. For a while, she stashed things in the ash collector beneath an unused fireplace in the dining room, but couldn’t shake the fear that she would die suddenly and we would forget what she had buried there, sending it up in smoke. I forget what she buried there. Not the rings we called knuckle-dusters, with huge semiprecious stones—topaz, amethyst, tourmaline—on tiny gold and silver mounts. They weren’t valuable or even wearable, but they were very pretty, and most of them had been given to her by friends or sent in padded envelopes across vast distances of space and time by relatives who thought she should have them. The person they’d belonged to must have died, but who that was I don’t know.

The secret drawer, which she had designed herself after consulting the carpenter, was where she kept her most precious items: her naturalization papers; a list of how much I weighed during the first six months of my life; various documents testifying to her abilities as a bookkeeper; and the gun.

“Remember it’s here,” she said, the one time she showed it to me. “And remember my jewels. Don’t let your father’s second wife get her hands on them.”

“Ha!” called my dad from the hallway. “I should be so lucky.”

My mother smiled. “You’ll miss me when I’m gone.”

It was smaller than I’d imagined, silver with a pearl handle, like something a highwayman might proffer through a frilly sleeve during a slightly fey holdup. I knew it was illegal, but gun licensing wasn’t the issue then that it is now and it struck me as naughty in the order of, say, a white lie, rather than something genuinely criminal, like dropping litter in the street or parking on the double yellow lines outside the liquor store. She had it, she said, because “everybody had one.” I think she saw it as a jaunty take on the whole stuffy English notion of inheritance—just the thing for a woman to bequeath to her only daughter. My dad hated having it in the house and threatened, once, to throw it in the local arm of the Grand Union Canal.

“You’ll do no such thing!” my mother raged. “I’m very fond of that gun.”

• • •

IT WAS ABOUT A YEAR after this that she stood in the kitchen cooking the sausages, face flushed from the heat pulsing out of the grill. My dad was watching TV in the next room. “Go and change,” she had said when he came in from work, as she said every night. Without turning and in a voice so harsh and strange she sounded like a medium channelling an angry spirit, she said, “My father was a violent alcoholic and a pedophile who . . .” The rest is lost, however, because at the first whiff of trouble I burst loudly into tears like a cartoon baby.

Something unthinkable happened then. My mother, who at the slightest hint of distress on my part would mobilize armies to eliminate the cause, who routinely threatened to kill people on my behalf and who felt, I always thought, shortchanged that I never gave her an opportunity to show me exactly what she could do in this area, didn’t move across the floor to console me, but stood staring disconsolately into the mouth of the grill. “Your father cried, too, when I told him,” she said, and I could see there was consolation in this, her sense of being surrounded by weaklings. Abruptly I switched off the tears. My dad came in. We ate dinner as normal. We didn’t talk about it again for fifteen years.

Except that we did, of course. “The absence from conversation of a known quantity is a very strong presence,” wrote Margaret Atwood in Negotiating with the Dead, “as the Victorians realised about sex.”

“Don’t get kidnapped,” said my mother, whenever I left the house. “Don’t get abducted. Don’t get raped and murdered.”

“I’m only going to the shop,” I said, or later, over the phone from London, “to the office/Manchester/the loo.”

“So?” she said. “They have murderers in Manchester, don’t they?”

About once a week, she rang after a sleepless night and we went through the routine.

“I had a sleepless night.”

“What?”

“Someone broke into the house in the night and snatched you away.”

Or:

“Someone ran away with you on your way home from work.”

Or, simply:

“Your dirty washing.” The more ludicrous the cause, the better. Once, a personal best, a sleepless night about my flatmate’s dirty washing. I told him by way of a boast, “Look how much my mother loves me, so much she loses sleep over whether you have clean clothes or not.” I remember he giggled rather nervously.

Only occasionally her comic tone faltered. In the car on the way back from Oxford one day: “Don’t be cross with me—I had a sleepless night.”

I was instantly furious. “For God’s sake,” I said. “It was one date. ONE DATE.”

My mother looked at me ruefully. “I thought he might cut you up and put you under the floorboards.” This referred to a recent case in the news in which a man from Oxford had murdered his girlfriend and, folding her like a ventriloquist’s doll, stuffed her in a suitcase under his bed. The floorboards part was a flourish I think she got from Jack the Ripper.

“I’m not going to tell you anything if this is how you behave.”

Her contrition evaporated. A warning look. “People get abducted, don’t they? People get murdered.” And there it was in the car with us, the huge mauve silence at the edge of the known world. “These things happen.”

“Not to me, they don’t.”

She looked at me then with every ounce of love in her system.

“No, not to you.”

Mum, her sister Fay (in the huge hipster glasses) and Fay's ex-husband, Frank, in Trafalgar Square before I was born.

CHAPTER 2

South Africa, 1932–1960

THE OFFICIAL REASON my mother gave for leaving was politics. “I couldn’t stand the politics,” she said, and pointed to March 1960, when sixty-nine people had been killed in Sharpeville while protesting against apartheid. She had been to a couple of meetings, she said, and had to decide whether to stay and commit or leave altogether. This was the story as she told it.

No one in her family had ever been to England. Her father’s ancestry was Dutch. Her mother’s, she said, had been French. But like most English-speaking white people in the former colony, she had grown up thinking of England as a point of origin. She was a great reader and had plowed her way through the nineteenth-century English novels. She identified strongly with Jane Eyre, even more so with Bertha Mason, and not at all with Cathy, in Wuthering Heights, who she thought made a spectacle of herself, carrying on like that at the window. She would have sympathized with Virginia Woolf’s put-down of Katherine Mansfield, who was said to have appeared in ghost form after her death, which Woolf thought typical of the woman: to be caught leading such a “cheap posthumous life.” Her favorite Austen heroine was Elizabeth Bennet, for what she saw as her keen lack of hysteria.

I knew she had been born in Durban, in her auntie Kathy’s house, and that when she was two years old her mother had died of tuberculosis. I also knew that around the age of five her father had remarried. But of his second wife—where they met, who her family was, or anything much about her beyond her name, Marjorie—I knew nothing. My mother had no sympathy for her, although her life would seem to have been hard. She was pregnant for more or less a decade after marrying my grandfather, and my mother, like many eldest children in a family that size, was put in the position of surrogate parent to some of her half-siblings.

She never called them “half.” She called them “my brothers and sisters.”

If it struck me as odd that we never saw or heard from them, I didn’t dwell on it. Like most children, the life my parents led before I was born was a rumor I didn’t believe in. When I gave her childhood any thought at all, I thought it sounded kind of fun; like Cider with Rosie, but with deadlier wildlife.

My mother was tall, slim, not athletic exactly but aware of her own strength. She was very blond as a child, and no matter what she did with her hair, couldn’t get it to curl. This was the era of Shirley Temple, and my mother presented it to me as the tragedy of her childhood: lank hair. But she had large brown eyes and high cheekbones, and one day, as she left the schoolyard, two little boys shouted after her, “We love you, we love you!”

Math was her subject. She worked hard at school, each week competing for first place with a girl called Stella, but whereas Stella was gifted, said my mother, she had to work for it. She gave me a meaningful look. “Oh, cut it out,” I thought. She wanted to be a nurse, but the teacher took her aside and said, nonsense, you should be a doctor. Since most of her schooling took place in English-speaking Natal, in the southeast of the country, she never learned Afrikaans—which didn’t stop her, years later, startling Dutch guests around the pool in Majorca by trying to use it to engage them in small talk, while I slid behind my paperback and pretended to be Spanish.

“We love you, we love you!” Eight-year-old mum with her brother, Michael.

She sometimes referred to her father as Jimmy. He had worked in the gold mines or as an engine driver, and she was rather proud of the latter; of the two jobs, it’s the one she chose to list as his profession on her marriage certificate. She showed me a poem he had written once, which he had given to her when she left South Africa. It was called “Salutation to the Dawn” and was full of soppy descriptions of the sky and wildlife. “He probably copied it out of a book,” she said bitterly, a rare break in tone. Most of her recollections ran along jollier lines.

. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.