The end of September is a great time to have a birthday if you want to be a writer. Jane Austen might be December 16 and Shakespeare April 23 and Charles Dickens February 9, but for a sheer run of greatness, I challenge anyone to match September 23 through September 30--F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, T. S. Eliot, Marina Tsvetayeva, William Blake, and Miguel Cervantes. And, I used to add (to myself, of course), moi. There is also a gratifying musical backup--George Gershwin on the twenty-sixth, my very own birthday. I never hesitated to bring anyone who cared (or did not care) to know up to date on late September (Ray Charles, Dmitri Shostakovich) and early October (John Lennon) birthdays. It was rather like listing your horse's pedigree or your illustrious ancestors--not exactly a point of pride, but more a reassurance that deep down, the stuff was there, if only astrologically.

But in 2001, the year I turned fifty-two, whether or not the stuff was there astrologically, it did not seem to be there artistically. All those years of guarding my stuff--no drinking, no drugs, personal modesty and charm, good behavior on as many fronts as I could manage, a public life of agreeability and professionalism, and still when I sat down at the computer to write my novel, titled Good Faith, my heart sank. I was into the 250s and 260s, there were about 125 pages to go, and I felt like Dante's narrator at the beginning of The Divine Comedy. I had wandered into a dark wood. I didn't know the way out. I was afraid.

I tried hard not to be afraid in certain ways. Two weeks before my birthday, terrorists had bombed the World Trade Center in New York. Fear was everywhere--fear of anthrax, fear of nuclear terrorism, fear of flying, fear of the future. I felt that, too, more than I was willing to admit. I tried to remind myself of the illusory nature of the world and my conviction that death is a transition, not an end, to discipline my fears to a certain degree. And my lover and partner was diagnosed at about that time with heart disease and required several procedures. I feared that he might also undergo a sudden transition and I would be bereft of his physical presence, but I also believed that we were eternally joined and that there was no transition that would separate us. This is how we agreed to view his health crisis. Physical fears were all too familiar for me--I had been wrestling with them my whole life, but in the late 1990s, divorce, independence, horses, Jack, and a book called A Course in Miracles had relieved most of them.

When I sat down at my computer, though, and read what I had written the day before, I felt something new--a recoiling, a cold surprise. Oh, this again. This insoluble, unjoyous, and unstimulating piece of work. What's the next sentence, even the next word? I didn't know, and if I tried something, I suspected it would just carry me farther down the wrong path, would be a waste of time or worse, prolong an already prolonged piece of fraudulence. I wondered if my case were analogous to that of a professional musician, a concert pianist perhaps, who does not feel every time he sits down to play the perfect joy of playing a piece he has played many times. I had always evoked this idea hopefully for students--however such a musician might begin his concert, surely he would be carried away by his own technique and mastery; after a few bars, the joy contained in the music itself would supply the inspiration that was lacking only moments before. But I didn't know that. Maybe that sort of thing didn't happen at all.

I came up with all sorts of diagnoses for my condition. The state of the zeitgeist was tempting but I refused to be convinced.* I reminded myself that I had lived through lots of zeitgeists over the years, and the geist wasn't all that bad in California. The overwhelming pall of grief and fear and odor and loss reached us more or less abstractly. Unlike New Yorkers, we could turn it off and get back to work, or so it seemed. But perhaps I was sensitive to something other than events--to a collective unconscious reaction to those events that I sensed in the world around me? I felt scattered. Even after I lost my fascination with the images and the events, my mind felt dissipated and shallow. It didn't help that I was annoyed with everything other writers wrote about the tragedy. There was no grappling with its enormity, and everything everyone said sounded wrong as soon as they said it. After this should come only silence, it seemed, and yet I didn't really believe that. I believed that the world was not now changed for the worse--that anyone who had not reckoned upon the world to deliver such a blow, after lo these many years of genocide, mass murder, war, famine, despair, betrayal, death, and chaos, was naive. I believed at the time that if the world was a little changed, then perhaps it was changed for the better. The images had gone global, moving many individuals to look within and find mercy and compassion rather than hatred and anger. Hatred and anger were the oldest old hat, but mercy and compassion were something new. If there was more of those, and there seemed to be, then the turning point had actually been a turning point. Only time would tell. At any rate, surely talking was good, writing was good. Communicating was good, the antidote to the secrecy and silence the terrorists had attempted to foist upon us. Perhaps, I thought, I would stay scattered until the collective unconscious pulled itself together and raised itself up and put fear aside.

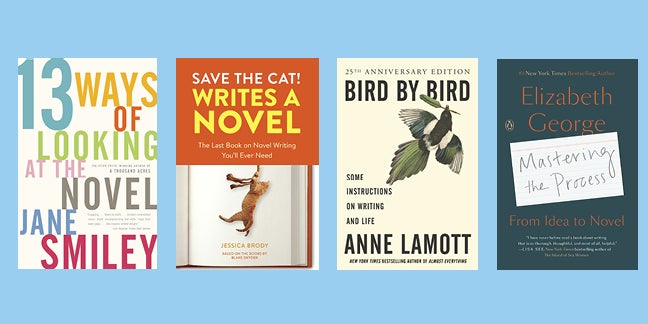

But really, events were events. I had known events and written through them, written about them, written in spite of them. I had grown up during the cold war, when obliteration seemed imminent every time the Russians twitched. I had an engagement photo of my parents from a newspaper; the headline of the article on the reverse side was "Russians Develop H-Bomb." Fear of terrorism, I thought, was nothing compared with the raw dread I had felt as a child. The problem with the novel was not outside myself, or even in my link to human consciousness. Perhaps, I thought, it was my own professional history. I had experienced every form of literary creation I had ever heard of--patient construction (A Thousand Acres), joyous composition (Moo, Horse Heaven), the grip of inspiration that seems to come from elsewhere (The Greenlanders), steady accumulation (Duplicate Keys), systematic putting together (Barn Blind), word-intoxicated buzz (The Age of Grief), even disinterested professional dedication (The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie Newton). I could list my books in my order of favorites, but my order of favorites didn't match anyone else's that I knew of, and so didn't reveal anything about the books' inherent value or even about their ease of composition. I didn't put too much stock in my preferences, or even in my memories of how it had felt to write them.

But I had penned a concise biography of Charles Dickens, and maybe I had learned from Dickens's life an unwanted lesson. I wrote the Dickens book because I loved Dickens, not because I felt a kinship with him, but after writing the book, it seemed to me that there was at least one similarity between us, and that was that Dickens loved to write and wrote with the ease and conviction of breathing. Me, too. When he took up each novel or novella, there might be some hemming and hawing and a few complaints along the way, but his facility of invention was utterly reliable and he was usually his own best audience. In the heat of composition, he declared almost every novel he wrote his best and his favorite, even if his preferences didn't stand. Toward the end of his life, though, his energy began to fail. When he was fifty, planning a new publication, he plunged rapidly into Great Expectations and wrote in weekly parts, modifying an earlier plan for the novel and producing a masterpiece largely because his journal needed it. When he began Our Mutual Friend a few years later, he was taxed almost beyond his powers. Several numbers were short, he complained of his lack of invention, and he didn't really like the novel much, though a case can be made (I have made it) that it is one of his most perfect. And he died in the middle of his last novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, having not quite mastered the whodunit form. Even Dickens, I thought, even Dickens faltered in the end, though you might say that he was careful and nurturing of his talents--abstemious and hardworking. He always deflected his fame a bit, wore it lightly. Was the lesson I had learned from Charles Dickens that a novelist's career lasts only a decade or two, can't be sustained much longer even by the greatest novelist (or most prolific great novelist) of all time?

Look at them all--Virginia Woolf, twenty-three or twenty-four years. George Eliot, twenty years. Jane Austen, twenty years, Dickens, twenty-four years, Thomas Hardy, fifty years of writing, but less than half of that novels. James Joyce, D. H. Lawrence, F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, Miguel Cervantes. Short short short. I had meant to write my whole life. Surely modern life and modern medicine and modern day care and modern technology and modern publishing would make Henry James the paradigmatic novelist, not Jane Austen. I wondered if novel-writing had its own natural life span and without knowing it, I had outlived the life span of my novel-writing career.

Another thing I learned about Dickens was that after 1862, he began to live a much more active life than he had before. In 1856, he left his wife in a scandalous divorce and took up with a much younger woman. Sometime in the very early 1860s, the younger woman disappeared. Some authorities think that she and her mother moved to France and that Dickens visited her there, in a small city or town, and that possibly she produced a child. Dickens's work was based in London, his family was near Chatham in Kent, and his beloved was in France. Dickens traveled back and forth incessantly, sometimes spending only a few days in each place. He also embarked on several arduous dramatic reading tours. It may be that such a schedule dissipated his energy or his concentration. I found myself in that, too. Once, when I lived in Ames, Iowa, where errands were easy and day care was exceptional, I had hours on end in which to marinate my day's work. After I moved to California, gave in to my obsession with horses, and became a single mother, to fritter away an hour meant to fritter away most of the day's allotted writing time. Distractions abounded, and they all seemed important. But then, I had always had children, I had always had something else to do during the day--not riding and horse care, but teaching and professorial responsibilities.

If to live is to progress, if you are lucky, from foolishness to wisdom, then to write novels is to broadcast the various stages of your foolishness. This was true of me. I took up each of my novels with unwavering commitment. I did not begin them by thinking I had a good subject for a novel. I began them by thinking that I had discovered important truths about the world that required communication. When I was writing Duplicate Keys, for example, a murder mystery, I was convinced of the idea that every novel is really some sort of mystery or whodunit because every novel is a retrospective uncovering of the real story behind the apparent story. I thought I might write mysteries for the rest of my life. When I was writing The Greenlanders, it was obvious to me that all novels were historical novels, patiently reconstructing some time period or another, recent or distant. Horse racing, medieval Greenland, farming, dentistry. I would get letters and reviews from all sorts of people who found themselves reading with interest about subjects they had never thought of before. But at the end of each novel, I would more or less throw down that lens along with that subject. My curiosity was always about how the world worked, what the patterns were, and what they meant. I was secular to the core, and I investigated moral issues with the dedication only someone who is literally and entirely agnostic would do--my philosophical stance was one of not knowing any answers and not believing that there were any answers.

While I was writing Horse Heaven, though, I embarked on a spiritual discipline that was satisfying and comforting. I came to believe in God and to accept a defined picture of Reality that took elements of Christianity and combined them with elements of Eastern religions. It was not an institutionalized religion, but it was a defined faith and had a scripture. It was called A Course in Miracles, and it completely changed the way I looked at the world.

The essential premise of A Course in Miracles is that God did not create the world and that the apparent mixture in the world of good and evil is an illusion; God is not responsible for apparent evil. In fact, the world itself and all physical manifestations are illusory, an agreed-upon conceit that is useful for learning what is true and real, but otherwise a form of dreaming--bad dreaming. The essential falsehoods of the world are that beings are separate from one another, that bodies are real and of primary importance, and that the physical preexists the spiritual. A Course in Miracles, like many Eastern religions, maintains that the world, all physical things, all elements of the universe, and all dimensions, including time, are a mental construct, and that the Mind or the Source preexists matter and is connected to itself all the time and in every way. It took me about three years to turn my image of the world upside down and to become comfortable with this new way of thinking. It wasn't hard, though it was disconcerting at the beginning. The payoff, other than my conviction that these ideas were true, was that I grew less fearful, more patient, less greedy, and more accepting. I greeted events more calmly as a rule, and didn't feel that old sense of vertigo that I had once felt much of the time. I got analyzed, or therapized, or counseled. My counselor shared my beliefs. Together we fixed my relationships and my worldview.

Copyright © 2006 by Jane Smiley. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.