In Haddam, summer floats over tree-softened streets like a sweet lotion balm from a careless, languorous god, and the world falls in tune with its own mysterious anthems. Shaded lawns lie still and damp in the early a.m. Outside, on peaceful-morning Cleveland Street, I hear the footfalls of a lone jogger, tramping past and down the hill toward Taft Lane and across to the Choir College, there to run in the damp grass. In the Negro trace, men sit on stoops, pants legs rolled above their sock tops, sipping coffee in the growing, easeful heat. The marriage enrichment class (4 to 6) has let out at the high school, its members sleepy-eyed and dazed, bound for bed again. While on the green gridiron pallet our varsity band begins its two-a-day drills, revving up for the 4th: "Boom-Haddam, boom-Haddam, boom-boom-ba-boom. Haddam-Haddam, up'n-at-'em! Boom-boom-ba-boom!"

Elsewhere up the seaboard the sky, I know, reads hazy. The heat closes in, a metal smell clocks through the nostrils. Already the first clouds of a summer T-storm lurk on the mountain horizons, and it's hotter where they live than where we live. Far out on the main line the breeze is right to hear the Amtrak, "The Merchants' special," hurtle past for Philly. And along on the same breeze, a sea-salt smell floats in from miles and miles away, mingling with shadowy rhododendron aromas and the last of the summer's staunch azaleas.

Though back on my street, the first shaded block of Cleveland, sweet silence reigns. A block away, someone patiently bounces a driveway ball: squeak . . . then breathing . . . then a laugh, a cough . . . "All riiight, that's the waaay." None of it too loud. In front of the Zumbros', two doors down, the streets crew is finishing a quiet smoke before cranking their machines and unsettling the dust again. We're repaving this summer, putting in a new "line," resodding the neutral ground, setting new curbs, using our proud new tax dollars-the workers all Cape Verdeans and wily Hondurans from poorer towns north of here. Sergeantsville and Little York. They sit and stare silently beside their yellow front-loaders, ground flatteners and backhoes, their sleek private cars-Camaros and Chevy low-riders-parked around the corner, away from the dust and where it will be shady later on.

And suddenly the carillon at St. Leo the Great begins: gong, gong, gong, gong, gong, gong, then a sweet, bright admonitory matinal air by old Wesley himself: "Wake the day, ye who would be saved, wake the day, let your souls be laved."

Though all is not exactly kosher here, in spite of a good beginning. (When is anything exactly kosher?)

I myself, Frank Bascombe, was mugged on Coolidge Street, one street over, late in April, spiritedly legging it home from a closing at our realty office just at dusk, a sense of achievement lightening my step, stiff hoping to catch the evening news, a bottle of Roederer-a gift from a grateful seller I'd made a bundle for-under my arm. Three young boys, one of whom I thought I'd seen before-an Asian-yet couldn't later name, came careering ziggy-zaggy down the sidewalk on minibikes, conked me in the head with a giant Pepsi bottle, and rode off howling. Nothing was stolen or broken, though I was knocked silly on the ground, and sat in the grass for ten minutes, unnoticed in a whirling daze.

Later, in early May, the Zumbros' house and one other were burgled twice in the same week (they missed some things the first time and came back to get them).

And then, to all our bewilderment, Clair Devane, our one black agent, a woman I was briefly but intensely "linked with" two years ago, was murdered in May inside a condo she was showing out the Great Woods Road, near Hightstown: roped and tied, raped and stabbed. No good clues left-just a pink while-you-were-out slip lying in the parquet entry, the message in her own looping hand: "Luther family. Just started looking. Mid-90's. 3 p.m. Get key. Dinner with Eddie." Eddie was her fiancé.

Plus, falling property values now ride through the trees like an odorless, colorless mist settling through the still air where all breathe it in, all sense it, though our new amenities-the new police cruisers, the new crosswalks, the trimmed tree branches, the buried electric, the refurbished band shell, the plans for the 4th of July parade-do what they civically can to ease our minds off worrying, convince us our worries aren't worries, or at least not ours alone but everyone's-no one's-and that staying the course, holding the line, riding the cyclical nature of things are what this country's all about, and thinking otherwise is to drive optimism into retreat, to be paranoid and in need of expensive "treatment" out-of-state.

And practically speaking, while bearing in mind that one event rarely causes another in a simple way, it must mean something to a town, to the local esprit, for its values on the open market to fall. (Why else would real estate prices be an index to the national well-being?) If, for instance, some otherwise healthy charcoal briquette firm's stock took a nosedive, the company would react ASAP. Its "people" would stay at their desks an extra hour past dark (unless they were fired outright); men would go home more dog-tired than usual, carrying no flowers, would stand longer in the violet evening hours staring up at the tree limbs in need of trimming, would talk less kindly to their kids, would opt for an extra Pimm's before dinner alone with the wife, then wake oddly at four with nothing much, but nothing good, in mind. Just restless.

And so it is in Haddam, where all around, our summer swoon notwithstanding, there's a new sense of a wild world being just beyond our perimeter, an untallied apprehension among our residents, one I believe they'll never get used to, one they'll die before accommodating.

A sad fact, of course, about adult life is that you see the very things you'll never adapt to coming toward you on the horizon. You see them as the problems they are, you worry like hell about them, you make provisions, take precautions, fashion adjustments; you tell yourself you'll have to change your way of doing things. Only you don't. You can't. Somehow it's already too late. And maybe it's even worse than that: maybe the thing you see coming from far away is not the real thing, the thing that scares you, but its aftermath. And what you've feared will happen has already taken place. This is similar in spirit to the realization that all the great new advances of medical science will have no benefit for us at all, though we cheer them on, hope a vaccine might be ready in time, think things could still get better. Only it's too late there too. And in that very way our life gets over before we know it. We miss it. And like the poet said: "The ways we miss our lives are life."

This morning I am up early, in my upstairs office under the eaves, going over a listing logged in as an "Exclusive" just at closing last night, and for which I may already have willing buyers later today. Listings frequently appear in this unexpected, providential way: An owner belts back a few Manhattans, takes an afternoon trip around the yard to police up bits of paper blown from the neighbors' garbage, rakes the last of the winter's damp, fecund leaves from under the forsythia beneath which lies buried his old Dalmatian, Pepper, makes a close inspection of the hemlocks he and his wife planted as a hedge when they were young marrieds long ago, takes a nostalgic walk back through rooms he's painted, baths grouted far past midnight, along the way has two more stiff ones followed hard by a sudden great welling and suppressed heart's cry for a long-lost life we must all (if we care to go on living) let go of . . . And boom: in two minutes more he's on the phone, interrupting some realtor from a quiet dinner at home, and in ten more minutes the whole deed's done. It's progress of a sort. (By lucky coincidence, my clients the Joe Markhams will have driven down from Vermont this very night, and conceivably I could complete the circuit-listing to sale-in a single day's time. The record, not mine, is four minutes.)

My other duty this early morning involves writing the editorial for our firm's monthly "Buyer vs. Seller" guide (sent free to every breathing freeholder on the Haddam tax rolls). This month I'm fine-tuning my thoughts on the likely real estate fallout from the approaching Democratic Convention, when the uninspirational Governor Dukakis, spirit-genius of the sinister Massachusetts Miracle, will grab the prize, then roll on to victory in November-my personal hope, but a prospect that paralyzes most Haddam property owners with fear, since they're almost all Republicans, love Reagan like Catholics love the Pope, yet also feel dumbfounded and double-crossed by the clownish spectacle of Vice President Bush as their new leader. My arguing tack departs from Emerson's famous line in Self-Reliance, "To be great is to be misunderstood," which I've rigged into a thesis that claims Governor Dukakis has in mind more "pure pocketbook issues" than most voters think; that economic insecurity is a plus for the Democrats; and that interest rates, on the skids all year, will hit 11% by New Year's no matter if William Jennings Bryan is elected President and the silver standard reinstituted. (These sentiments also scare Republicans to death.) "So what the hell," is the essence of my clincher, "things could get worse in a hurry. Now's the time to test the realty waters. Sell! (or Buy)."

In these summery days my own life, at least frontally, is simplicity's model. I live happily if slightly bemusedly in a forty-four-year-old bachelor's way in my former wife's house at 116 Cleveland, in the "Presidents Streets" section of Haddam, New Jersey, where I'm employed as a Realtor Associate by the Lauren-Schwindell firm on Seminary Street. I should say, perhaps, the house formerly owned by formerly my wife, Ann Dykstra, now Mrs. Charley O'Dell of 86 Swallow Lane, Deep River, CT. Both my children live there too, though I'm not certain how happy they are or even should be.

The configuration of life events that led me to this profession and to this very house could, I suppose, seem unusual if your model for human continuance is some Middletown white paper from early in the century and geared to Indiana, or an "ideal American family life" profile as promoted by some right-wing think tank-several of whose directors live here in Haddam-but that are just propaganda for a mode of life no one could live without access to the very impulse-suppressing, nostalgia-provoking drugs they don't want you to have (though I'm sure they have them by the tractor-trailer loads). But to anyone reasonable, my life will seem more or less normal-under-the-microscope, full of contingencies and incongruities none of us escapes and which do little harm in an existence that otherwise goes unnoticed.

This morning, however, I'm setting off on a weekend trip with my only son, which promises, unlike most of my seekings, to be starred by weighty life events. There is, in fact, an odd feeling of lasts to this excursion, as if some signal period in life-mine and his-is coming, if not to a full close, then at least toward some tightening, transforming twist in the kaleidoscope, a change I'd be foolish to take lightly and don't. (The impulse to read Self-Reliance is significant here, as is the holiday itself-my favorite secular one for being public and for its implicit goal of leaving us only as it found us: free.) All of this comes-in surfeit-near the anniversary of my divorce, a time when I routinely feel broody and insubstantial, and spend days puzzling over that summer seven years ago, when life swerved badly and I, somehow at a loss, failed to right its course.

Yet prior to all that I'm off this afternoon, south to South Mantoloking, on the Jersey Shore, for my usual Friday evening rendezvous with my lady friend (there aren't any politer or better words, finally), blond, tall and leggy Sally Caldwell. Though even here trouble may be brewing.

For ten months now, Sally and I have carried on what's seemed to me a perfect "your place and mine" romance, affording each other generous portions of companionship, confidence (on an as-needed basis), within-reason reliability and plenty of spicy, untranscendent transport-all with ample "space" allotted and the complete presumption of laissez-faire (which I don't have much use for), while remaining fully respectful of the high-priced lessons and vividly catalogued mistakes of adulthood.

Not love, it's true. Not exactly. But closer to love than the puny goods most married folks dole out.

And yet in the last weeks, for reasons I can't explain, what I can only call a strange awkwardness has been aroused in each of us, extending all the way to our usually stirring lovemaking and even to the frequency of our visits; as if the hold we keep on the other's attentions and affections is changing and loosening, and it's now our business to form a new grip, for a longer, more serious attachment-only neither of us has yet proved quite able, and we are perplexed by the failure.

Last night, sometime after midnight, when I'd already slept for an hour, waked up twice twisting my pillow and fretting about Paul's and my journey, downed a glass of milk, watched the Weather Channel, then settled back to read a chapter of The Declaration of Independence-Carl Becker's classic, which, along with Self-Reliance, I plan to use as key "texts" for communicating with my troubled son and thereby transmitting to him important info-Sally called. (These volumes by the way aren't a bit grinding, stuffy or boring, the way they seemed in school, but are brimming with useful, insightful lessons applicable directly or metaphorically to the ropy dilemmas of life.)

"Hi, hi. What's new?" she said, a tone of uneasy restraint in her usually silky voice, as if midnight calls were not our regular practice, which they aren't.

"I was just reading Carl Becker, who's terrific," I said, though on alert. "He thought that the whole Declaration of Independence was an attempt to prove rebellion was the wrong word for what the founding fathers were up to. It was a war over a word choice. That's pretty amazing."

She sighed. "What was the right word?"

"Oh. Common sense. Nature. Progress. God's will. Karma. Nirvana. It pretty much all meant the same thing to Jefferson and Adams and those guys. They were smarter than we are."

"I thought it was more important than that," she said. Then she said, "Life seems congested to me. just suddenly tonight. Does it to you?" I was aware coded messages were being sent, but I had no idea how to translate them. Possibly, I thought, this was an opening gambit to an announcement that she never wanted to see me again-which has happened. ("Congested" being used in its secondary meaning as: "unbearable.") "Something's crying out to be noticed, I just don't know what it is," she said. "But it must have to do with you and I. Don't you agree?"

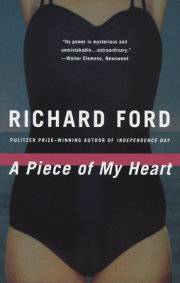

Copyright © 1996 by Richard Ford. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.