When we were small, my sister Isabella and I used to wonder whether Alba had murdered our father.

Murdered him, and then made up the suicide story.

We'd be in the kitchen, hunting for food, two skinny girls, ten and twelve. Murdered. We'd let that possibility hang in the air, to see if anything crashed or shattered, but nothing ever moved. The house remained perfectly still.

"Who knows, anyway," we'd say, to finish it off. We didn't really want to know. If she had done it, eventually they would come and lock her up.

It was bad enough, what had happened already. Dad vanishing, like a card in a trick.

We'd hear the keys in the door. She'd come in smiling, wearing her green dress and sandals, her arms full of groceries.

There she was: Alba. Our mother. The Murderer.

"Want a prosciutto sandwich, darlings?"

When we were that small, things shifted proportions all the time: the really dangerous stuff shrunk, curled up in a ball so that we could juggle it, study it closely, let it drop from our hands the minute it began to bother us.

It was a silent agreement between my sister and me. To move on, to survive.

To eat that sandwich.CHAPTER ONE

Careful now. Watch what you do.

You keep staring at the living room, you don't think you can fol- low this task. It feels like sacrilege to alter its order, like rummaging a temple.

How long has this dark red armchair been sitting across from the threadbare sofa, right next to the painted lampshade? How many years has the faded rug sat on these stone tiles? Ren?e's portrait hung on the wall? The opaline vase stood on the mantelpiece?

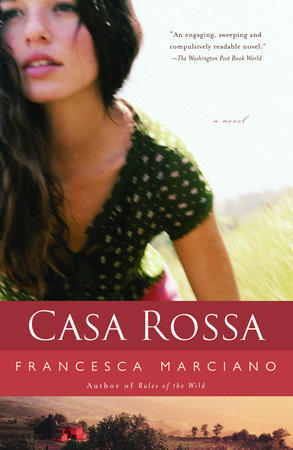

My grandfather bought this house in the late twenties. It was a crumbling farmhouse then, nobody wanted it. My mother grew up here. My sister and I did, too.

Casa Rossa has been my family house for over seventy years.

I know its smell like I know the smell of cut grass. Its map is imprinted in me, I can walk it blindfolded.

Why did I think these objects would stay like this forever and that I could always come back, find the chair and the sofa and the rug and the painting in their place? That way I assumed I could always reenact all the different moments that shaped our story. Like the day when Ren?e was sitting for my grandfather on the wicker chair and, as he was painting another one of her portraits, she told him about Muriel. The summer day Oliviero came for lunch and sat outside on the patio under the trellis and fell in love with my mother. The times my sister lay awake at night, wrapped in her hatred, fearing every noise. Or the night I took Daniel Moore in here for the first time. I opened the door and showed him this room. This rug, this faded sofa, that yellowing lampshade. The room smelled of firewood. "This is it," I said.

I hoped it would stay like this forever, so that, by coming back and finding everything still arranged exactly as I had left it, I would believe I had secured my history in a safe place. Inside a shrine, where nothing would get lost. Just as prayers are never lost in a church. One can always go back and light another candle.

As I walk across the ground floor of Casa Rossa, as I move from the large kitchen into the living room, then through the big wooden door into my grandfather's studio, I look around, I count my steps, I mark my territory as if it's the last time I will ever do this. And, guess what. It is.

I talk out loud to myself-like I always do when I'm scared. Careful now, watch what you do. Everything, from now on, will be final and surprisingly quick.

The movers will arrive and wait for me to give them a sign. Then they will heft the table, then the sofa, they will roll up the rug and take down the painting. They will wrap the furniture in blankets and tie it with rope. They will blindfold and choke the familiar shapes and will pile them up one on top of the other in the truck. An armrest will show from under the blanket. The stain on its faded fabric will look pathetic. The scratches on the table legs, the pale circle a cup had once left on its top: all these familiar marks will look spooky now, like scars. One didn't notice them so much before. But it will be impossible to look at them now without shame. You will have to admit that these things have turned into what they have always been but which you always refused to see: a pile of sad, old junk.

Once every single piece of furniture and every single box are loaded onto the truck, this house, stripped bare in a single morning, will go back to being mute. A white canvas, where someone else will write their story.

That's how fast our memories disintegrate.

I've been procrastinating about calling the movers, of course. Who wouldn't? It's like phoning in your own death sentence and prodding the executioner.

Instead I've been wandering around the rooms in a daze, touching surfaces, sizing things up. Every time I open a drawer or look in the back of an armoire, some new discovery stuns me. I keep turning between my fingers what I have just found, as if expecting it to talk to me. An old dusty ribbon (a hat? gift wrapping?), a newspaper clipping from the fifties, the obituary page (whose death are we looking at here?), a single light-blue silk shoe, custom-made in Paris (Ren?e's?), a tiny photograph in black-and-white, of a group of young people huddled together on a beach in thirties-style bathing suits (which one is my grandfather?), a single page from a letter (no date, no signature, written in French).

It's like trying to trace the history of an Egyptian mummy from her ring, a few glass beads, bits of broken pottery, a faded inscription. Yes, she was a merchant's wife-no, a pharaoh's sister, or maybe a high priestess. History demands a plot with a proper beginning and a proper end.

This is not a story about what we know, nor about what we have.

This story is about what gets lost on the way.

My mother, Alba, rings me twice a day from her house in Rome. She wants to know how I'm proceeding with the move.

"Oh," I say gingerly, "I'm not quite ready yet. I still have to go through all the drawers upstairs in the bedrooms. There are all these papers, photographs, you have no idea how-"

"Just chuck everything in the boxes," she interrupts. "You'll never get out alive if you start looking at everything. Those people said they want to move in next week."

"It's all right. They have the house for life now. They can wait another day or two. By the way, I found your wedding dress."

"Oh my

God."

"It doesn't even look like a wedding dress. I only recognized it from of the photos."

"You found those as well?" she asks.

"Yes. Everything was kind of stuffed inside a box on top of the armoire in your room. There were hats, printed wedding invitations, an envelope full of pictures. Papa looks like this smart kid with glasses. Like a math genius or something. Why didn't you wear a long white dress?"

"Oh, I don't know. It was a country wedding. . . . I kept it simple," she sighs, impatient with me already. "I remember it was a pretty dress."

"Knee-length, full skirt. Tiny poppies embroidered here and there. Fifties-style, you know. I'm wearing it right now."

"You are?"

"It barely fits me, but it makes this whole process a bit more fun. You know, wearing something so nice."

"Alina," she sighs . . . . "are you okay doing this on your own? Do you want me to come down? I could get on the train tomorrow if you need me."

She asks this question twice a day, her voice full of dread that I'll say yes.

"No, I'm fine. You would only get in the way."

"Are you sure? I'll come if-"

"No, really. I'm actually enjoying it. It's kind of . . . therapeutic."

I don't hear anything coming from her end, so I add:

"It's like, you don't even begin to realize someone you love is really dead until you see their body go underground. It's part of the process."

"Jesus, you are morbid," she says, but I can feel her relief: she can stay in Rome.

I always knew she wouldn't have anything to do with sorting out old, forgotten boxes. Alba has never been big on remembering.

Puglia is the heel of Italy, the thinnest strip of land between two seas. Lorenzo, my grandfather, said it was exactly this-the refraction of the sun hitting the water on both sides-that made the light of Puglia so rich and warm. He had chosen to buy a house there because of it. He needed to paint in that light, he said.

Way before it was called Casa Rossa, the house had been a crumbling farmhouse-

a masseria-built in the eighteen-hundreds, surrounded by a wall in the midst of an olive grove among the open fields in the countryside south of Lecce.

Copyright © 2002 by Francesca Marciano. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.