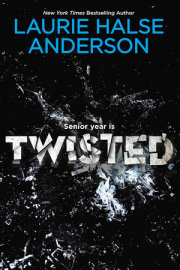

1

So she tells me, the words dribbling out with the cranberry muffin crumbs, commas dunked in her coffee.

She tells me in four sentences. No, five.

I can’t let me hear this, but it’s too late. The facts sneak in and stab me. When she gets to the worst part

. . . body found in a motel room, alone . . .

. . . my walls go up and my doors lock. I nod like I’m listening, like we’re communicating, and she never knows the difference.

It’s not nice when girls die.

2

“We didn’t want you hearing it at school or on the news.” Jennifer crams the last hunk of muffin into her mouth. “Are you sure you’re okay?”

I open the dishwasher and lean into the cloud of steam that floats out of it. I wish I could crawl in and curl up between a bowl and a plate. (My stepmother) Jennifer could lock the door, twist the dial to SCALD, and press ON.

The steam freezes when it touches my face. “I’m fine,” I lie.

She reaches for the box of oatmeal raisin cookies on the table. “This must feel awful.” She rips off the cardboard ribbon. “Worse than awful. Can you get me a clean container?”

I take a clear plastic box and lid out of the cupboard and hand it across the island to her. “Where’s Dad?”

“He had a tenure meeting.”

“Who told you about Cassie?”

She crumbles the edges of the cookies before she puts them in the box, to make it look like she baked instead of bought. “Your mother called late last night with the news. She wants you to see Dr. Parker right away instead of waiting for your next appointment.”

“What do you think?” I ask.

“It’s a good idea,” she says. “I’ll see if she can fit you in this afternoon.”

“Don’t bother.” I pull out the top rack of the dishwasher. The glasses vibrate with little screams when I touch them. If I pick them up, they’ll shatter. “There’s no point.”

She pauses in mid-crumble. “Cassie was your best friend.”

“Not anymore. I’ll see Dr. Parker next week like I’m supposed to.”

“I guess it’s your decision. Will you promise me you’ll call your mom and talk to her about it?”

“Promise.”

Jennifer looks at the clock on the microwave and shouts, “Emma—four minutes!”

(My stepsister) Emma doesn’t answer. She’s in the family room, hypnotized by the television and a bowl of blue cereal.

Jennifer nibbles a cookie. “I hate to speak ill of the dead, but I’m glad you didn’t hang out with her anymore.”

I push the top rack back in and pull out the bottom. “Why?”

“Cassie was a mess. She could have taken you down with her.”

I reach for the steak knife hiding in the nest of spoons. The black handle is warm. As I pull it free, the blade slices the air, dividing the kitchen into slivers. There is Jennifer, packing store-bought cookies in a plastic tub for her daughter’s class. There is Dad’s empty chair, pretending he has no choice about these early meetings. There is the shadow of my mother, who prefers the phone because face-to-face takes too much time and usually ends in screaming.

Here stands a girl clutching a knife. There is grease on the stove, blood in the air, and angry words piled in the corners. We are trained not to see it, not to see any of it.

. . . body found in a motel room, alone . . .

Someone just ripped off my eyelids.

“Thank God you’re stronger than she was.” Jennifer drains her coffee mug and wipes the crumbs from the corners of her mouth.

The knife slides into the butcher block with a whisper. “Yeah.” I reach for a plate, scrubbed free of blood and gristle. It weighs ten pounds.

She snaps the lid on the box of cookies. “I have a late settlement appointment. Can you take Emma to soccer? Practice starts at five.”

“Which field?”

“Richland Park, out past the mall. Here.” She hands the heavy mug to me, her lipstick a bloody crescent on the rim. I set it on the counter and unload the plates one at a time, arms shaking.

Emma comes into the kitchen and sets her cereal bowl, half-filled with sky-colored milk, next to the sink.

“Did you remember the cookies?” she asks her mother.

Jennifer shakes the plastic container. “We’re late, honey. Get your stuff.”

Emma trudges toward her backpack, her sneaker laces flopping. She should still be sleeping, but my father’s wife drives her to school early four mornings a week for violin lessons and conversational French. Third grade is not too young for enrichment, you know.

Jennifer stands up. The fabric of her skirt is pulled so tight over her thighs, the pockets gape open. She tries to smooth out the wrinkles. “Don’t let Emma con you into buying chips before practice. If she’s hungry, she can have a fruit cup.”

“Should I stick around and drive her home?”

She shakes her head. “The Grants will do it.” She takes her coat off the back of the chair, puts her arms in the sleeves, and starts to button up. “Why don’t you have one of the muffins? I bought oranges yesterday, or you could have toast or frozen waffles.”

(Because I can’t let myself want them) because I don’t need a muffin (410), I don’t want an orange (75) or toast (87), and waffles (180) make me gag.

I point to the empty bowl on the counter, next to the huddle of pill bottles and the Bluberridazzlepops box. “I’m having cereal.”

Her eyes dart to the cabinet where she had taped up my meal plan. It came with the discharge papers when I moved in six months ago. I took it down three months later, on my eighteenth birthday.

“That’s too small to be a full serving,” she says carefully.

(I could eat the entire box) I probably won’t even fill the bowl. “My stomach’s upset.”

She opens her mouth again. Hesitates. A sour puff of coffee-stained morning breath blows across the still kitchen and splashes into me.

Don’t say it—don’tsayit. “Trust, Lia.”

She said it. “That’s the issue. Especially now. We don’t want . . .”

If I weren’t so tired, I’d shove

trust and

issue down the garbage disposal and let it run all day.

I pull a bigger bowl out of the dishwasher and put it on the counter. “I. Am. Fine. Okay?”

She blinks twice and finishes buttoning her coat. “Okay. I understand. Tie your sneakers, Emma, and get in the car.”

Emma yawns.

“Hang on.” I bend down and tie Emma’s laces. Doubleknotted. I look up. “I can’t keep doing this, you know. You’re way too old.”

She grins and kisses my forehead. “Yes you can, silly.”

As I stand up, Jennifer takes two awkward steps toward me. I wait. She is a pale, round moth, dusted with eggshell foundation, armed for the day with her banker’s briefcase, purse, and remote starter for the leased SUV. She flutters, nervous.

I wait.

This is where we should hug or kiss or pretend to.

She ties the belt around her middle. “Look . . . just keep moving today. Okay? Try not to think about things too much.”

“Right.”

“Say good-bye to your sister, Emma,” Jennifer prompts.

“Bye, Lia.” Emma waves and gives me a small berridazzle smile. “The cereal is really good. You can finish the box if you want.”

3

I pour too much cereal (150) in the bowl, splash on the two-percent milk (125). Breakfast is themostimportantmealoftheday. Breakfast will make me a cham-pee-on.

. . .

When I was a real girl, with two parents and one house and no blades flashing, breakfast was granola

topped with fresh strawberries, always eaten while reading

a book propped up on the fruit bowl. At Cassie’s house

we’d eat waffles with thin syrup that came from maple

trees, not the fake corn syrup stuff,

and we’d read the funny pages. . . . No. I can’t go there. I won’t think. I won’t look.

I won’t pollute my insides with Bluberridazzlepops or muffins or scritchscratchy shards of toast, either. Yesterday’s dirt and mistakes have moved through me. I am shiny and pink inside, clean. Empty is good. Empty is strong.

But I have to drive.

. . . I drove last year, windows down, music cranked, first Saturday in October, flying to the SATs. I drove so

Cassie could put the top coat on her nails. We were secret

sisters with a plan for world domination, potential

bubbling around us like champagne. Cassie laughed. I

laughed. We were perfection.

Did I eat breakfast? Of course not. Did I eat dinner the night before, or lunch, or anything?

The car in front of us braked as the traffic light turned yellow, then red. My flip-flop hovered above the pedal. My edges blurred. Black squiggle tingles curled up my spine and wrapped around my eyes like a silk scarf. The car in front of us disappeared. The steering wheel, the dashboard, vanished. There was no Cassie, no traffic light. How was I supposed to stop this thing?

Cassie screamed in slow motion.

::Marshmallow/air/explosion/bag::

When I woke up, the emt-person and a cop were frowning. The driver whose car I smashed into was

screaming into his cell phone.

My blood pressure was that of a cold snake. My heart was tired. My lungs wanted a nap. They stuck me with a needle, inflated me like a state-fair balloon, and shipped me off to a hospital with steel-eyed nurses who wrote down every bad number. In pen. Busted me.

Mom and Dad rushed in, side by side for a change, happy that I was not dead. A nurse handed my chart to my mother. She read through it and explained the disaster to my father and then they fought, a mudslide of an argument that spewed across the antiseptic sheets and out into the hall. I was stressed/overscheduled/manic/no—depressed/no—in need of attention/no—in need of discipline/in need of rest/in need/your fault/your fault/fault/fault. They branded their war on this tiny skin-bag of a girl.

Phone calls were made. My parents force-marched me into (hell on the hill) New Seasons. . . .

Cassie escaped, as usual. Not a scratch. Insurance more than covered the damage, so she wound up with a fixed car and new speakers. Our mothers had a little talk, but really all girls go through these things and what are you going to do? Cassie rescheduled for the next test and got her nails done at a salon, Enchanted Blue,

while they locked me up and dripped sugar water into my empty veins. . . . Lesson learned. Driving requires fuel.

Not Emma’s Bluberridazzlepop cereal. I shiver and pour most of the soggy mess down the disposal, then set the bowl on the floor. Emma’s cats, Kora and Pluto, pad across the kitchen and stick their heads in the bowl. I draw a cartoon face with a big tongue on a sticky note, write YUMMY, EMMA! THANKS! and slap it on the cereal box.

I eat ten raisins (16) and five almonds (35) and a greenbellied pear (121) (= 172). The bites crawl down my throat. I eat my vitamins and the crazy seeds that keep my brain from exploding: one long purple, one fat white, two poppyred. I wash everybody down with hot water.

They better work quick. The voice of a dead girl is waiting for me on my phone.

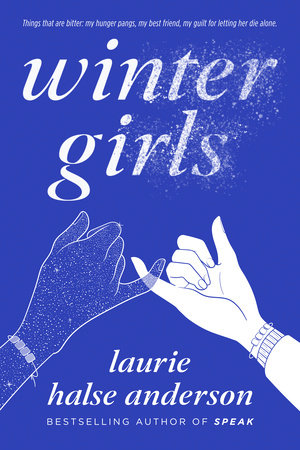

Copyright © 2009 by Laurie Halse Anderson. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.